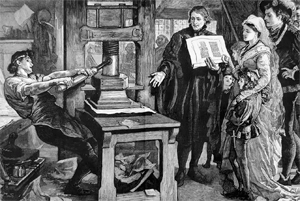

William Caxton, an English businessman and diplomat, was based for much of his time in Europe. After seeing printing presses in Germany he set one up in Bruges, where he had settled. Returning to England, he set up the first English press in London initially to print copies of his own book, although the first book recorded from his press was Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Prior to this, books had been enormously expensive, usually hand-copied by monks and often meticulously and ornately decorated. Books were so precious they were sometimes fixed by chains to metal rods on shelves to deter theft in what were known as chained libraries. No wonder Jankyn is cross when the Wife of Bath rips pages from his book in The Wife of Bath’s Prologue. While Sujata Bhatt maintains in her poem ‘A Different History’ that it is ‘a sin to shove a book aside/with your foot,/a sin to slam books down/hard on a table’, clearly our treatment of books now, particularly almost-disposable paperbacks, is very different, and that is down to William Caxton in the 15th century.

William Caxton, an English businessman and diplomat, was based for much of his time in Europe. After seeing printing presses in Germany he set one up in Bruges, where he had settled. Returning to England, he set up the first English press in London initially to print copies of his own book, although the first book recorded from his press was Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Prior to this, books had been enormously expensive, usually hand-copied by monks and often meticulously and ornately decorated. Books were so precious they were sometimes fixed by chains to metal rods on shelves to deter theft in what were known as chained libraries. No wonder Jankyn is cross when the Wife of Bath rips pages from his book in The Wife of Bath’s Prologue. While Sujata Bhatt maintains in her poem ‘A Different History’ that it is ‘a sin to shove a book aside/with your foot,/a sin to slam books down/hard on a table’, clearly our treatment of books now, particularly almost-disposable paperbacks, is very different, and that is down to William Caxton in the 15th century.

The history of books, their role and people’s attitudes to them are the subject matter of Emma Smith’s new book Portable Magic. Smith is Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Oxford University and her work is always vibrant, insightful and approachable. You could read her book This is Shakespeare, which is based on her excellent Shakespeare lectures, which you can access here. Portable Magic is not about Shakespeare, but is a celebration of all books, international and carefully researched. Here you can read an enticing review of the book.

One writer to benefit posthumously from the publication of books was John Donne, who wrote privately in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His work was published later and is extraordinary for its range, encompassing playful erotic poetry and sombre religious poems. Common features are complexity of thought, highly skilled wordplay and the stretching of metaphor almost to breaking point. These ideas are known as the characteristics of what became known as metaphysical poetry. One of my favourites is ‘The Sun Rising’ – see how he overturns the conventional reverence for the sun, and ends the poem in the opposite position from the start, but moves between the two by logic:

One writer to benefit posthumously from the publication of books was John Donne, who wrote privately in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His work was published later and is extraordinary for its range, encompassing playful erotic poetry and sombre religious poems. Common features are complexity of thought, highly skilled wordplay and the stretching of metaphor almost to breaking point. These ideas are known as the characteristics of what became known as metaphysical poetry. One of my favourites is ‘The Sun Rising’ – see how he overturns the conventional reverence for the sun, and ends the poem in the opposite position from the start, but moves between the two by logic:

Busy old fool, unruly sun,

Why dost thou thus,

Through windows, and through curtains call on us?

Must to thy motions lovers’ seasons run?

Saucy pedantic wretch, go chide

Late school boys and sour prentices,

Go tell court huntsmen that the king will ride,

Call country ants to harvest offices,

Love, all alike, no season knows nor clime,

Nor hours, days, months, which are the rags of time.

Thy beams, so reverend and strong

Why shouldst thou think?

I could eclipse and cloud them with a wink,

But that I would not lose her sight so long;

If her eyes have not blinded thine,

Look, and tomorrow late, tell me,

Whether both th’ Indias of spice and mine

Be where thou leftst them, or lie here with me.

Ask for those kings whom thou saw’st yesterday,

And thou shalt hear, All here in one bed lay.

She’s all states, and all princes, I,

Nothing else is.

Princes do but play us; compared to this,

All honour’s mimic, all wealth alchemy.

Thou, sun, art half as happy as we,

In that the world’s contracted thus.

Thine age asks ease, and since thy duties be

To warm the world, that’s done in warming us.

Shine here to us, and thou art everywhere;

This bed thy centre is, these walls, thy sphere.

He is, says Katherine Rundell in a recent article, the perfect poet not just for his times, but for our own.