The Future Rests on Women

Errol John spends a page and a half describing the setting at the beginning of his play, giving designers (and readers of the script) a clear visualisation of the ‘Two dilapidated buildings’ in the yard. The care he takes with these stage directions indicates their importance. The tight packed yard, even described with an ironically comic tone as one building ‘can claim the distinction of having once been painted’, indicates shabby poverty and enclosed forced intimacy. In that way it can be seen as a microcosm of the island of Trinidad itself.

The Claustrophobia of the Yard

Neighbours live cheek by jowl, trying to scrabble out the best existence they can. Their inevitable intrusion into each other’s lives is made apparent in the episodic bickering between Sophia and Mavis. Charlie’s story is one of thwarted ambition, so it is no surprise that the play revolves around Ephraim’s desire to escape the island and its lack of opportunities. The endless cycle of non-advancement is clear in his description of his work as a trolleybus driver:

Eight hours a day – up Henry Street – down Park Street – Tragarete Road – St James Terminus – Turn it round! – Back down town again! – And around again! O Gord!

The structure of the sentence, its list of familiar street names and repetition of ‘round’ and ‘again’ make his life seem as repetitious as a mouse cage wheel.

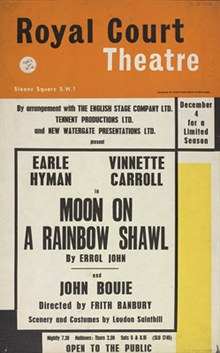

John knew all about this urge to leave Trinidad and the Caribbean, emigrating to England as part of the Windrush generation to seek a future as an actor. Frustrated with the limited opportunities for black actors, he entered Moon on a Rainbow Shawl into The Observer’s playwriting competition in 1957. Winning that competition, the play was performed at the Royal Court Theatre in London, a theatre with a long and proud tradition of promoting new writing. The play does not tell us if Ephraim makes a success of his emigration, but John makes his departure and charged and complex decision.

John knew all about this urge to leave Trinidad and the Caribbean, emigrating to England as part of the Windrush generation to seek a future as an actor. Frustrated with the limited opportunities for black actors, he entered Moon on a Rainbow Shawl into The Observer’s playwriting competition in 1957. Winning that competition, the play was performed at the Royal Court Theatre in London, a theatre with a long and proud tradition of promoting new writing. The play does not tell us if Ephraim makes a success of his emigration, but John makes his departure and charged and complex decision.

Ephraim the Hero

Ephraim is established as a sympathetic figure. He is clearly loved by the twelve-year-old Esther and he looks out for her in the manner of an older brother or an uncle. He is noticeably sharp with Mavis, telling her to ‘Cut that!’ when she makes dubious insinuations about what ‘private lessons’ he might be teaching Esther. Later, with ‘quiet authority’, he intervenes to demand that Mavis ‘Have a little respect for the child.’ He is also the most encouraging about Esther’s academic achievements. ‘Winning scholarship’, he tells her, should make her ‘on top of the world’. Significantly he introduces the idea of leaving the island, but in this case encouraging Esther to do so:

Yer know Esther. When yer grow up – it would be kind of nice of yer could go away and study – on a island scholarship or something. Come back – big! Yer know! Make everybody respect yer.

As the play develops, we see that Ephraim is here projecting his own aspirations onto Esther, but John is also reminding the audience that Esther is actually the character most likely to make a success of emigration – she has the ‘brains’. However, his evasiveness about his ability to accompany Esther to the band concert introduces an uneasy note which is an early hint of his own plans for departure.

In a play where there are many examples of male characters ruled by their physical desires, notably Mavis’ American clients, Ephraim is presented in the early scenes embodying a different type of masculinity. Notable here is his taking charge of the baby, cradling him and tenderly whispering ‘Dream yer dreams, little man. Dream yer dreams.’ Moon on a Rainbow Shawl is a play about dreams and the cost of dreams. It is also to Ephraim that John gives the most lyrical speeches of the play, from which it takes its title:

Esther – if yer have yer head screw on right – No matter where yer go – One night – sometime – Yer reach up – yer touch that moon.

His lines are about hope and aspiration, however challenging the odds.

Ephraim the Zero

But of course this version of Ephraim is ultimately compromised. Avoiding easy, straightforward characterisation, John challenges the audience’s initial perception of Ephraim by the revelation of his attitude to Rosa, his lover. John places hints about Rosa’s pregnancy as early as Act 1 Scene 1, Sophia questioning whether Ephraim indeed ‘never give’ Rosa ‘a thing’ and asking her whether she ‘tell him yet?’ However, it is not until Act 2 that the matter is spoken of directly.

The languorous bedroom scene is suffused by sexuality – Rosa, ‘dressed in a pale pink slip’ groans ‘happily – luxuriously’, places Ephraim’s hand ‘on her breast’ and begs him to ‘Make love! … Please!’ Ephraim’s resistance to these moves acutely signals the tension until he reveals his ‘Passport! Ticket! Them few traveller’s cheques!’ intended for his journey ‘Four thousand miles across the sea!’

His response to Rosa’s revelation ‘I’m pregnant’, highlighted by the pause which follows, is to dismiss her statement as a ‘TRAP!’ In a striking contrast with his tenderness and understanding with Esther and the baby early in the play, John now reveals his selfish side, at times abhorrent. Not only does he dismiss talk of the baby as ‘that damn nonsense’ to Rosa, but truly shockingly at the end of the play rejects it in an outburst to Sophia:

So what? The baby born! It live! It dead! It make no damn difference to me!

The audience understands Ephraim’s frustration with his lack of opportunities in Trinidad, where even his promotion to Inspector would only allow him to:

Stand at bus stop. Hop on the trolley. Check the tickets. Hop off the trolley!

However his brutal rejection of Rosa and his unborn child are difficult for the audience to accept, showing the richness and ambiguity of John’s characterisation. Even his guilt-ridden story of the heartless abandonment of his grandmother fails to change his mind.

Loafers, Wasters and Exploiters

None of the other men in the play elicit much admiration. From the American servicemen punters to the flashy Prince, Mavis attracts men impatient for sexual gratification. Old Mack, who has made a limited financial success of his life on the island, owning a café and renting out houses, is presented as someone who exploits his neighbours, attempting and failing to build a grandiose home for himself rather than ‘build a decent kitchen… Fix up the bathroom… Put on a roof’ for his tenants.

However, his first appearance in the play is humiliating as he begs for the attentions of Rosa. John uses both dialogue and stage action to render him ridiculous, begging Rosa to ‘Come back to my place’ as she pulls away from his attempted embrace. Old Mack ‘stumbles and falls awkwardly to his knees’ while ‘pressing hard against her flank’. The visual image is one of pathetic subjugation, capped off by Sophia’s comment:

Well! Put a candle in his hand, and I would say that it was the Baptist preacher giving baptism.

John’s stage directions confirm the image of Old Mack’s embarrassment:

Then he tries, almost comically, like a Chaplinesque drunk, to compose himself. He turns quickly, walking with a forced dignity through the gate and out towards the street.

The comic mockery of Old Mack is important in later somewhat mitigating the seriousness of Charlie’s theft of money from his café, but Charlie too is one of John’s failing male figures. He steals not for himself, but for Esther’s education, but he is brought to theft because he is unable to hold a job and work for the money. Sophia laments his lack of work and greets his drunken return with ‘Yer damn good fer nothing you!’

It is his dialogue with Ephraim that reveals the additional layers of Charlie’s characterisation. Now a part-time repairer of cricket bats, the audience discovers that Charlie himself was once a successful fast bowler – ‘They don’t make them that fast these days’, he boasts, in true paceman style. Based on Errol John’s own father, George John, who took 133 first class wickets at an average a little over 19, Charlie too has had his career limited by inter-island rivalry and racist attitudes. Charlie’s anger at his treatment on a tour in Jamaica ensured that it was the ‘last inter-colony series I ever play.’ We can understand his disappointment, though he now dismisses it as ‘long ago.’ It is clear though that he has never really recovered. As he tells Ephraim:

You don’t know yet, boy – what life is like – when things start to slide from under yer.

However, his chance of a permanent job coaching cricket seems to be scuppered by his theft, conducted so ineptly that he left his tell-tale recognisable hat behind.

Female Strength and Hope

With so many feckless or fleeing men, John puts the strength and the hope of the play in its women. Even the cruelly abandoned Rosa refuses to be characterised as a victim. Ephraim ‘teach me good’ about men, she says, adding ‘Now I’m ready for anything!’ She asserts the independence of women from men:

With so many feckless or fleeing men, John puts the strength and the hope of the play in its women. Even the cruelly abandoned Rosa refuses to be characterised as a victim. Ephraim ‘teach me good’ about men, she says, adding ‘Now I’m ready for anything!’ She asserts the independence of women from men:

Wedding rings too cheap to have to kiss one man foot for.

The child in her womb becomes a symbol of hope for the future rather than a burden on its single mother.

Although Sophia and Mavis spar throughout the play, they parallel each other, representing different methods of survival when opportunities are limited. Sophia is highly disapproving of Mavis’ prostitution, telling Old Mack that he ought to ‘be ashame’ of letting her live ‘among decent people’. However, as the landlord says, ‘She pays her rent’, and ‘on time.’ And Mavis is successful at securing Prince at the end of the play, the only other character with Ephraim of achieving their aim.

The Heart of the Play

Sophia is the central pillar of strength in the play, supporting not only her husband and daughter, but confidante to Ephraim and Rosa too. John’s introductory stage directions note that ‘Hard times and worry have lined her’, and that she is ‘The backbone of her family’. That is clear in her management of Esther, but she takes a quasi-parental role with Rosa and Ephraim too. In the absence of steady work for Charlie, it is her work as a washerwoman which keeps the family going. This is clear not just from the action of the play but visually in the setting too:

Sophia’s washing, a riot of colour, blocks out the view to the street – the line bellying with the weight of damp clothing.

Though the clothes on the line are not her own, the image represents Sophia – hard working, dominant and full of vibrancy.

Esther blames Sophia for Charlie’s’ crime, suggesting it has come as a result of her ‘Always pushing him and pushing him. And making him feel shame in front of all kinds of people’. Indeed, there are several occasions when she harangues Charlie for his failures. However, she also comforts Charlie after his confession, like a mother with her child, telling him to ‘Hush, boy! Hush! Don’t cry!’ and promising that ‘Sophie will find a way.’ She also admits her deep affection for Charlie to Rosa, telling her that ‘I know the many times he was worth a bowlful of tears’ to contrast with Rosa’s ‘I ent fillin’ a my eye with water fer no man.’

Similarly, while she is often demanding of Esther, John also indicates her parental care as she ‘proudly’ looks at Esther’s needlework and asks her to ‘Show it to yer father.’ As John’s initial description states, Sophia can ‘be hard, unyielding’, but he also makes clear her deep loving nature. The hardness is necessary for survival – not just her own, but her family’s.

Esther’s Light

The last line of the play is spoken by Esther and John’s accompanying stage direction is crucial in understanding her role in the play:

[Her] call has warmth – a certain immediacy – strength. It should give the impression that the future could still be hers.

Her name is also a key indicator – Esther comes from the Old Persian word for ‘star’. She is John’s guiding spark of light and hope for the future. Charlie reinforces this when he tells her that ‘One day, little girl – you are going to be a star!’ The image also chimes with her opening dialogue with Ephraim about the moon and her ability to ‘reach up’ and ‘touch that moon’ some day.

It is education which marks Esther out from the other characters. Her scholarship offer is significant, marking her out as a child of recognised potential and therefore opening up opportunities beyond those available to the other inhabitants of the yard. Ephraim, Sophia and Charlie also remark on her intelligence at different times, reinforcing the audience’s awareness of her possibilities. She voices it herself too, questioning received knowledge with ‘I want to know the truth.’ The scholarship, though is perhaps threatened by Charlie’s arrest.

Yet she is just a child. John’s use of Janette and the other children remind the audience of Esther’s youth despite her responsibilities helping her mother and her potential future. She is innocent in a place where innocence is difficult to maintain. Ephraim’s protective reproof of Mavis’ crude jokes is an important reminder of this. Despite the offer of a scholarship, there remain ‘So many things we find we have to get’, which creates the financial burden leading to Charlie’s theft of the money from Old Mack.

John’s final stage direction highlights this fragility of the hope which Esther represents. There is the ‘warmth’ and ‘strength’, but also an important modal in ‘the future could still be hers’. It remains a tenuous possibility, and the final sound image is of ‘the last trolley as it hisses by’, representing the ceaseless limitations of the island from which Ephraim has escaped.

There is light and hope at the end of the play, but it is flickeringly distant, like a star.