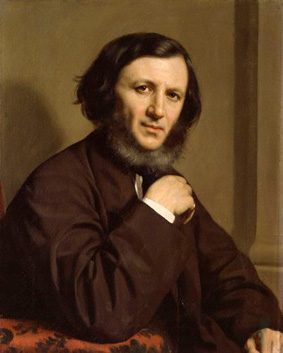

An anthology of key poems by Browning, with some supporting notes and essays: Browning Anthology

Who’s Listening?

Browning’s Dramatic Auditors

Browning’s verse is filled with fascinating characters – the arrogant duke, the embittered painter, the vitriolic monk, the chasing lover, the dying bishop are just a few of the speakers among his dramatic monologues.

Browning’s interest in the dramatic monologue is not a surprise, as other poets around him, such as Tennyson, also experimented with them. But Browning’s reputation in some way depends on the form; it is notable that the entry on dramatic monologue in MH Abrams’ A Glossary of Literary Terms refers to Browning as having ‘perfected’ this type of poem. His success here is perhaps paradoxically related to his lack of success in an area of keen interest to him: dramatic writing. Browning took a strong interest in the theatre and badgered such great actors of the day such as Kean and Macready to produce his plays. Macready did produce and star in Strafford, which ran to five performances, but thereafter resisted Browning’s blandishments, and despite writing further dramas, Browning enjoyed no theatrical success.

Browning’s interest in the dramatic monologue is not a surprise, as other poets around him, such as Tennyson, also experimented with them. But Browning’s reputation in some way depends on the form; it is notable that the entry on dramatic monologue in MH Abrams’ A Glossary of Literary Terms refers to Browning as having ‘perfected’ this type of poem. His success here is perhaps paradoxically related to his lack of success in an area of keen interest to him: dramatic writing. Browning took a strong interest in the theatre and badgered such great actors of the day such as Kean and Macready to produce his plays. Macready did produce and star in Strafford, which ran to five performances, but thereafter resisted Browning’s blandishments, and despite writing further dramas, Browning enjoyed no theatrical success.

Where Browning’s fully fledged dramas failed, his dramatic monologues, in a much more concentrated form, have enjoyed enormous acclaim. Each is a mini-drama in itself. In each, Browning has created, as Abrams says, a character ‘in a specific situation at a critical moment’. The duke is in the last stages of wedding negotiations; the painter is forced to consider reasons for his lack of popular success; the monk is driven to distraction by the saintliness of a fellow brother; the lover is taking stock in the never-ending quest for love’s fulfilment; the bishop is on his deathbed.

The Audience

A speech alone, made in however intense a situation, is not drama. The great theatre director Peter Brook’s simplest definition of drama is an action happening ‘whilst someone else is watching’. After the performer and the performance, the final point of the triangle to enable drama to happen, is the audience.

So who, in Browning’s monologues, is watching, or more accurately in this case, listening? In some of the poems, we learn quite specifically who is being addressed. It becomes plain that the person being given a guided tour of the Duke’s artworks in ‘My Last Duchess’ is a representative, perhaps a secretary, of the Count whose daughter the Duke hopes to marry. ‘The Bishop’ who ‘Orders His Tomb’ is addressing those responsible for the sepulchre – his sons. Other audiences are less certain. ‘Pictor Ignotus’ is talking to someone who has an interest in, and knowledge of, art and the art world, whereas the title of ‘Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister’ suggests there is no auditor.

The Reader as Listener

However, in all these, even in ‘Soliloquy’, there is a listener – the reader. As readers, we become the confidants of Browning’s characters, we are entrusted with their views, their secrets. Whether we are put in the position of the pursued lover in ‘Love in a Life’, the Renaissance art aficionado in ‘Pictor Ignotus’ or the invisible audience in the ‘Soliloquy’, we are characterised ourselves by the way the speaker addresses us.

For the monologue to work as drama, readers need to feel that they are being addressed, and Browning is a master of manipulating verse in ways which create the sense of live, conversational speech. The monologues are peppered with vocal tags, ‘oh’s and ‘ah’s. There are rhetorical questions, exclamations and caesurae marking pauses for thought, like struggling to remember the name of the bridge in ‘A Toccata of Galuppi’s’, which is ‘arched by …what you call/ … Shylock’s bridge’. Browning is a master of meter, creating subtle shifts to imitate the patterns and rhythms of conversation. Note for example the use of parenthesis, commas and dashes in Pictor Ignotus’ line: ‘Nor will I say I have not dreamed (how well!)/ Of going – I, in each new picture – forth’. This is a man talking, and thinking as he talks; this has the effect of drawing the reader in as his listener.

The Painter’s Audience

But to whom does the disillusioned painter address his long speech? The ‘specific situation’ is indicated towards the end of the poem: the wording suggests that the speech takes place in situ, as the painter refers to ‘These endless cloisters’ he has painted on the immovable ‘damp wall’s travertine’ rather than portable canvas. You are standing in front of the painter’s work in a Florentine church – perhaps you’ve just wandered in and found him at work, asked him a question or dropped a comment about Raphael, and are subjected to 72 lines of bitterness. This does seem likely, as the first line sounds as if he has been stung to defend himself: ‘I could have painted pictures like that youth’s/ Ye praise so.’ The praise of the ‘youth’, a term used by the speaker that is disparaging as well as emphasising novelty and vigour, shows that you have some knowledge of art and your conversation with this less remarked painter confirms it. It is also likely that Pictor Ignotus would not express his views in such detail and at such length unless he felt that his auditor understood. This level of shared understanding is crucial to the poem.

It means that the listener understands art and appreciates the attraction of being able to portray ‘Each passion’ with a hand that effortlessly ‘flung’ paint onto the canvas. Such a listener would also recognise the Europe-wide fame available to artists, their work desired at all points of the compass by exalted people. It also suggests, though, that the listener might well be included in the painter’s scornful perception of the commercial art world, where people ‘buy and sell our pictures’ as a commodity, like ‘garniture and household-stuff’. This would make this section of the poem particularly barbed, but in the listener’s praise of ‘the youth’, the painter has perhaps recognised someone merely following the latest trends in art. This becomes an attack on the listener as well as a defence of the painter’s choices. It is easy to judge the painter as cowardly, but by this understanding of the listener’s position we are also invited to understand, even more so in the days of Tracey Emin’s bed and Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, the potential flaws in the commercial art world that follows fashion. The reader is forced into a reconsideration of the painter and the poem because the artist has assumed artistic understanding in the listener.

Soliloquy

‘Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister’ is a little different, in that the listener is not specifically characterised – the reader is almost subject to fierce whispers from round a pillar in the cloisters. This tone is established by the inarticulate rage of ‘G-r-r-r’ and insults like ‘Swine’s Snout’. This intemperate monk is so open about his loathing for Brother Lawrence that he seems to assume sympathy in his auditor; there is no fear of condemnation. His relationship with his audience is very much like that of Shakespeare’s Richard III, delighting in his villainy. There is a similar kind of energy and provocative humour; there may be shock at the pettiness of ‘close-nipped’ flowers to thwart fruiting and moral condemnation at his plans with a ‘scrofulous French novel’, but these plans are so wildly inappropriate for a monk that it’s funny. His verve draws us in; his imitation of the dullness of Lawrence’s conversation makes us appreciate his vivacity. His sensual appreciation the women’s ‘Steeping tresses’ is more attractive than Lawrence’s obsequious plans to gift half his melon crop ‘to the Abbot’s table’. This energy drives the poem from its first ‘G-r-r-r’ to its last and puts the listener in an ambiguous position. As detached readers we can see moral iniquity, but as listeners, we are taken so fully into the monk’s confidence and treated to such an energetic account, we are likely to sympathise with wicked energy rather than pious saintliness.

The Bishop and his Family

There’s a similar tension in ‘The Bishop Order His Tomb’, which is made immediately apparent when the Bishop addresses his listeners as ‘Nephews – sons mine…’ This supposedly celibate bishop seems to have passed off these men as more distant relatives during his life, and only on his deathbed can he acknowledge them as his sons. It’s an embarrassing truth which fits in with the secular worldliness he reveals, his rivalry with ‘Old Gandolf’, his love of ‘peach-blossom marble’, ‘lapis lazuli’ and the more sensual delights of ‘mistresses with great smooth marbly limbs’.

As the Bishop sets out his grandiose plans for his sepulchre, Browning has included a number of implicit stage directions which are very revealing. The most significant indicates the departure of the sons: ‘Well go! …/… and, going, turn your backs…’ At this crucial moment, the listeners, his sons, turn and leave. Why do they do so? Are they finally disgusted by the Bishop’s greed and vainglorious demands? While comprehensible, such silent abandonment is still an uncharitable act towards a dying man. They have been accused of having eyes which ‘glitter’ with hope of inheritance, waiting for the old man’s death. This too is an unfavourable interpretation of the auditors; in comparison with these two alternatives, the Bishop’s self-knowledge and deathbed energy might be seen more favourably. The poem shares some of the ambiguity of the ‘Soliloquy’, where a consideration of the identity of the auditors influences the response to the speaker.

Drama in Browning’s Poems

Browning’s dramatic speakers are energetic, complex and fascinating; we can see that in each poem the dramatic situation in which the poet places them inevitably includes the listener who is addressed. In each case, the reader becomes the listener and identifying that listener leads to further nuances and implications in the understanding of the poems.

References:

A Glossary of Literary Terms, MH Abrams, pub. Holt, Rhinehart and Winston

The Empty Space, Peter Brook, pub. Penguin

A version of this article first appeared in emag Issue 65, September 2014.