This week the revered Oxford English Dictionary has revealed the latest words to be added to its lists, all of which will feature in the third edition currently under preparation. Some of those words have emerged from recent political debates. Key among them are:

Wokery:

Progressive or left-wing attitudes or practices, esp. those opposing social injustice or discrimination, that are viewed as doctrinaire, self-righteous, pernicious, or insincere

and

Chumocracy:

A culture characterized or dominated by influential networks of close friends. In later use (chiefly British Politics): spec. government or the exercise of power characterized by the appointment of friends and associates to positions of authority, without proper regard to their qualifications or to due process

One of the additions makes you wonder what took them so long. This one is ‘Gradgrindian’, drawn from Charles Dickens’ novel Hard Times published in 1854, which begins with a focus on the central character Thomas Gradgrind, a schoolmaster who in an ‘inflexible, dry, and dictatorial’ voice, insists on an education based on ‘nothing but Facts’, to the exclusion of imagination, creativity and joy. Gove, Williamson, Keegan take note.

Here’s an article about the most recent additions.

The Politics of Definition

We all rely from time to time on dictionaries. They are our unbiased arbiters of meaning which, in dry academic tones, sift through perceived understanding to give us a true definition of the words of our language.

Have you ever stopped to wonder if that is quite true? Exactly who is that arbiter and what are their principles? Just as in our speech and writing we choose words for a specific context and aim for a particular effect, there is a context behind the choice of every word selected for the dictionary, and there is a choice of which definition to promote.

Women’s Lost Words

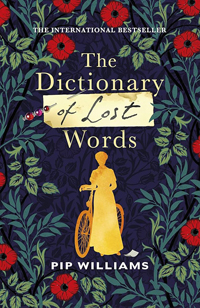

As a dictionary exercises control of the language, every choice made is both a linguistic and a political act. This is a realisation picked up and explored in Pip Williams’ novel The Dictionary of Lost Words. Based on careful research and fact, the novel focuses on the creation of the first edition of the OED, initially a project by the Philological Society begun in 1857, but with publishing not begun until 1884, such was the volume of the work.

As a dictionary exercises control of the language, every choice made is both a linguistic and a political act. This is a realisation picked up and explored in Pip Williams’ novel The Dictionary of Lost Words. Based on careful research and fact, the novel focuses on the creation of the first edition of the OED, initially a project by the Philological Society begun in 1857, but with publishing not begun until 1884, such was the volume of the work.

Into that genuine Oxford history Williams inserts her fictional heroine, the daughter of one of the lexicographers involved, who picks up the slips of paper which have been discarded or have fallen from the tables. These are the ‘lost words’ of the title and a key one, again factually, is ‘bondmaid’. Under the tables, picking up the litter, while men sit at the tables making decisions, Esme is a bright young woman restrained by the misogyny of her times. As this review suggests, the novel

… casts light on the many ways, both subtle and blatant, in which male supremacy is reflected in the language we speak and in the authority we assign to those who define its terms.

Helen Sullivan in The Guardian describes the novel as a ‘gentle, hopeful story’ offering a feminist consideration of the history of the OED and indeed the control of the English language. Williams raises the idea that our use of language is inevitably gendered:

Williams writes that her novel “began as two simple questions. Do words mean different things to men and women? And if they do, is it possible that we have lost something in the process of defining them?”

The Meaning of Everything

The Meaning of Everything

There is another book on the history of the OED, titled The Meaning of Everything. This one is a factual history, by Simon Winchester, and details the idiosyncrasies of those, led by Scottish lexicographer James Murray, who received submissions and sorted definitions. The project began life in a corrugated metal garden shed they called the Scriptorium, which is the term used for a room in medieval European monasteries where monks copying and illuminate of manuscripts.

The Continuing Life of the OED

The publication of the latest updates to the dictionary demonstrate that the OED is still going strong after those ambitious beginnings in 1857. The second edition, published in 1989, encompasses 20 volumes, 21,730 pages, and 59 million words. The online version takes up 540 million megabytes. As the third edition is in preparation, how large will that be when it is finished? It might be useful to have a list of the words that have disappeared since the previous edition.

You can look up the Oxford English Dictionary online, where there is a history section and a clarification of why the OED is so important:

As a historical dictionary, the OED is very different from dictionaries of current English, in which the focus is on present-day meanings. You’ll still find present-day meanings in the OED, but you’ll also find the history of individual words, sometimes from as far back as the 11th century, and of the language—traced through 3.5 million quotations, from classic literature and specialist periodicals to film scripts, song lyrics, and social media posts.