It’s the end of the year with the new one just around the corner. We may face that with different degrees of optimism or pessimism depending on our circumstances and worldview. For Hanif Kureishi it’s particularly bittersweet, alive and writing, but with a sense of self that has been ‘completely eradicated’ by the fall he suffered just over a year ago.

It’s the end of the year with the new one just around the corner. We may face that with different degrees of optimism or pessimism depending on our circumstances and worldview. For Hanif Kureishi it’s particularly bittersweet, alive and writing, but with a sense of self that has been ‘completely eradicated’ by the fall he suffered just over a year ago.

Paralysis

He guest edited the popular BBC Radio 4 Today programme on Boxing Day, exactly a year since his devastating accident. He spoke honestly about the difficulties he has faced through months of hospital treatment:

You realise quite quickly that your body doesn’t belong to you any more … that you are changed, washed, poked and prodded by nurses and doctors, random people all the time.

You give up any sense of privacy: of your body, of your mind, of your soul, of anything about you … it’s completely eradicated.

Almost completely paralysed, he now has to dictate his writing, mainly to his son, who does the writing for him, whereas he used to sit for hours at his own desk:

I had to find a completely new way to write; I can’t sit at my desk for hours … I can’t use my hands, I can’t use a pen. So I just have to say it.

It’s not hard to understand how that change has been debilitating for an independent, radical thinker and writer. It’s reminiscent of Jean-Dominique Bauby’s book, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, written after a stroke and a 20-day coma. That book was written by Bauby blinking his left eyelid to choose letters on a screen to choose letters.

At least Kureishi can talk freely, but it is clearly still a great struggle, as is demonstrated in this article from The Independent following his radio appearance, much of which was recorded in hospital.

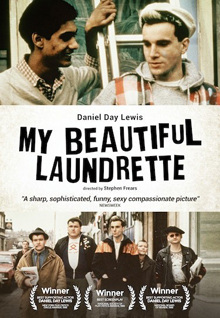

My Beautiful Laundrette

It was the film of his screenplay My Beautiful Laundrette which really launched Kureishi into the public consciousness. Televised in 1985, it broke all kind of taboos because it did not just portray a homosexual relationship, but showed an interracial one. At a time of the Thatcher Conservative government, with tensions about immigration and oppression of homosexuality, it was a radical film to put on television. By turns funny, moving and violent, it focuses on the Pakistani community in London, developing both legal and illegal businesses while under attack from right-wing racists. It features a very young Daniel Day-Lewis in one of the lead roles.

It was the film of his screenplay My Beautiful Laundrette which really launched Kureishi into the public consciousness. Televised in 1985, it broke all kind of taboos because it did not just portray a homosexual relationship, but showed an interracial one. At a time of the Thatcher Conservative government, with tensions about immigration and oppression of homosexuality, it was a radical film to put on television. By turns funny, moving and violent, it focuses on the Pakistani community in London, developing both legal and illegal businesses while under attack from right-wing racists. It features a very young Daniel Day-Lewis in one of the lead roles.

One of the key features of the film is that, despite his racial sympathies, Kureishi’s portrayal of the British Pakistani community is honest and avoids easy assumptions. In this article, journalist Kenan Malik argues that Kureishi’s work ‘helped liberate British Asians from their imposed identities’, where those identities we imposed by themselves or by British attitudes to them.

Kureishi himself commented on the contrary reactions to his work:

Islamic critics would say, ‘You shouldn’t wash dirty linen in public’. And the left would say, ‘You should not attack minority communities’.” These are sentiments that have only strengthened in the years since.

You can read more about Hanif Kureishi, his work and the critical response on the British Council site.

And here you can keep up with his writing from hospital and since, The Kureishi Chronicles.