Maurice Shadbolt

Shadbolt’s story is rooted in the colonial history of New Zealand and its wide sweep considers attitudes to land, family relationships and memory. The central encounter between the Pakeha (white New Zealander of European descent) and the Maori is an ironic reversal of the original colonial encounter.

Greenstone

Written as a narrative with three formal sections, there are a number of clear stages in the development of the story. The first clear hinge, opening up a new direction, is Jim’s discovery of the greenstone adzes in the neglected hills behind the family farm. These relics of Maori habitation indicate a previously unconsidered history of the land the farm occupies. It is a sudden entry into the story; it is notable that the five-page opening which establishes the family and the farm is entirely a Pakeha story, without any reference to Maori. The farmer’s attack on the scrub, which he feels he must ‘hack… down, grub out the roots’, can be read as a metaphor for his disregard for the land’s past.

The initial five pages are clearly focused on ‘possession of the land’, with the narrator puzzling about his father’s expression ‘got the place for a song’ and the father’s pride that the land ‘was his, by sweat and legal title’. The father walks his visitors around the farm to ‘share his satisfaction’ and he tells the narrator that having ‘some land I could call my own’ kept him going in the battles of the First World War. The narrator refers to the farm as his father’s ‘green kingdom’. These details are telling. While they suggest a deep connection between the farmer and his land, it is significant that the idea of ‘possession’ is exclusive, bought with money and held in law. Possessions held in that way can also be sold, as he considers that he ‘could sell out for a packet’. Such ideas of monetary and legal ownership of land are very different from Maori land traditions and Shadbolt explores that tension. It is a tension that is also apparent in the father’s attitude to the greenstone discovered by his son. He knows about greenstone, where it comes from, but also dismisses it as ‘Maori stuff’ while considering that there ‘Might be some money’ in it. He is aware of the monetary value of greenstone, but there is no acknowledgement on the deep spiritual significance of the stone to Maori culture.

The Arrival of the Maori

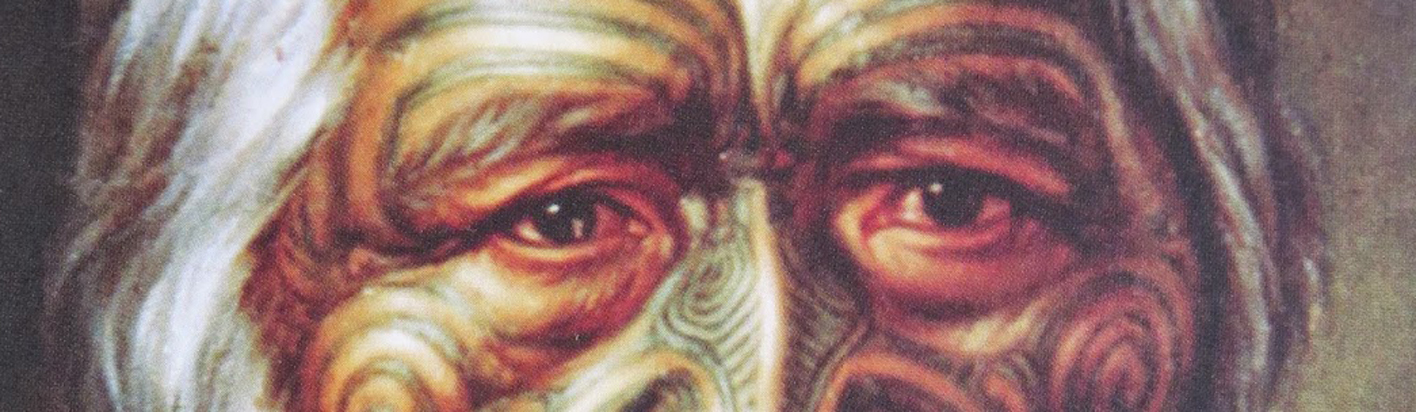

The second key shift in the story is the arrival of the Maori themselves in the second part, which makes the farmer realise that ‘the people before’ are not the Pakeha farmers from whom he bought the land, but the last indigenous people to live there, who can trace their ancestry to that place. In the conversation with Tom Taikaka, there is an uncomfortable tacit awareness of how Maori presence was ended, ‘when the European took the land.’ Shadbolt shows how this encounter differs from the original colonial encounter. The Maori have even telephoned ahead and Tom is presented continuously with adjectives and adverbs like ‘smiling’, ‘pleasantly’, ‘patient’ and ‘politely’ while he hopes that his party are ‘not troubling’ the farmer and his family. In contrast, the farmer at first refuses to shake hands, addresses the group as ‘you people’ and speaks ‘suspiciously’. Yet the Maori want to stake no claim, but to ‘go across your land’, up to the neglected hills where their ancient pa used to stand.

Of course this is a post-colonial encounter, where land ownership is recorded under Pakeha laws, and the Maori therefore arrive as supplicants. Tom is aware of this; in a way he must be polite. History has rolled on in New Zealand. Tom’s ease with English and even his name reflect this, with his English first name and Maori family name. Tom’s awareness of the direction of historical travel is also movingly apparent in Jim’s act of attempted restitution, offering to Tom the greenstone adzes, as he recognises that ‘these are really yours’. It is an astonishingly mature realisation by the boy, but Tom, ‘who really wanted the greenstone’, returns them to Jim. Like the land itself, he acknowledges that the adzes are ‘yours now’ and that he has ‘got no claims here any more’. History has forced Tom to accept the total dispossession of the Maori.

However, the Maori’s enduring connection to the land, and their different attitudes towards it when compared with the farmer’s, become clear. Tom, who has never visited the place before, can identify features of the landscape and even direct the farmer’s perspective so that he sees his land in a different way. It is a land over which Maori tribes battled for generations and Tom has a mental map of the land’s geography and history from stories – the culture, the history, the significances have been handed down by oral tradition. Tom, placing his feet on the land for the first time, has a complete affinity with it. He has brought an ancient elder to witness again, in his final days, the place he was born into, and evicted from. The sudden spark of life in the old man when he recognises the hill of the pa demonstrates its enduring significance to him.

The Death of the Old Man

The death of the iwi elder has been foreshadowed in the first part of the story by the discovery of bones and a human skull in one of the caves by the narrator and his brother. On their return, Tom simply and unapologetically says that the old man ‘died last might… So we left him up there’. It creates the possibility that this was the whole purpose of the journey and it reiterates the indelible bond between the Maori and the land which persists despite the passing of time, sale and resale, legal documents. Although Shadbolt deliberately provides no detail, it is clear that Maori death and burial traditions are also at wide variance from Pakeha practice. A police search ‘scoured the hills’ but ‘discovered no trace of a burial’ – the language indicates an exhaustive search, but its failure creates a mystery. Shadbolt leaves the reader with a sense of the rightness of the old man’s burial, back where he was born, on land to which he was utterly connected but which is now neglected.

Forgiveness

The end of the story, particularly the final line, is a puzzle. What is it which the narrator won’t forgive? What has his brother done? Like their father’s experience of sustaining himself in war by thinking of his ‘kingdom’, the roots of the unspoken rift are in warfare and land. Jim too has focused his mind while under fire in the Second World War by thinking of ‘That old place of ours.’ Jim, once the excited boy with ‘bright’ eyes of excitement about his discovery of the greenstone and Tom’s stories, has clung to those memories. yet he now speaks of them with casual insouciance, casually referring to ‘that old Maori’ and ‘those greenstones’ which he only ‘seem[s] to remember trying to give away’. They are now just a ‘souvenir’.

The narrator, of course, was the one who gave up school to work the farm with his father, allowing his younger brother to study and ultimately leave farming to become ‘a lecturer at the university’. Not only does his academic brother claim some kind of connection back to that farm, but he does so in a casual offhand way. Perhaps that is why the narrator feels that something has been stolen from him.

Narrative methods to consider:

- First person narration

- Foreshadowing

- Structure

- Characterisation

- Mystery