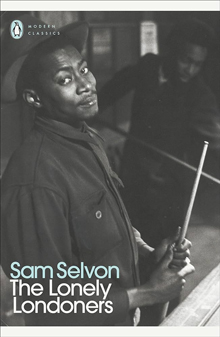

A dramatisation of Sam Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners has opened, to warm reviews, at London’s Jermyn Street Theatre. As a novel which explores the difficulties faced by the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants into Britain, of whom Selvon was one, it is a powerful book. Its range of vibrant characters and episodic structure which includes colourful anecdotes lends itself well to dramatic treatment, though there are other aspects which are harder to transform, like the ten-page section describing the London summer which has no punctuation at all, merging image into image.

A dramatisation of Sam Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners has opened, to warm reviews, at London’s Jermyn Street Theatre. As a novel which explores the difficulties faced by the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants into Britain, of whom Selvon was one, it is a powerful book. Its range of vibrant characters and episodic structure which includes colourful anecdotes lends itself well to dramatic treatment, though there are other aspects which are harder to transform, like the ten-page section describing the London summer which has no punctuation at all, merging image into image.

Adapting English

The radical move in 1956, when the novel was first published, was to write it in Creolised English patois – not just the characters’ dialogue, but the whole narration. Selvon had attempted to write the novel in Standard British English but found it frustrating and unsuccessful, as it ‘couldn’t carry the essence of what I wanted to say’. Things fell into place when he began to write in his own idiom, which gives a much clearer perspective to his central narrative figure, Moses. It also creates empathy, as the narrative is written for an understanding ear and takes the reader into its confidence.

In that way Selvon gives clear expression to the difficulties the migrants faced in finding accommodation and jobs, when they were often faced with hostility and the politicians in Parliament are ‘making rab’ about immigration. The connections with today’s immigration debates and the slow progress of the Windrush Compensation Scheme are clear, making the dramatisation a timely and relevant one.

The Standard’s review of the production praises its spirit, arguing that ‘there is something celebratory in the men’s camaraderie and their enduring love for London, even though it seems to scorn them.’ The Arts Desk calls the production an ‘intimate, energetic stage adaptation’ and hopes that it will attract new readers to appreciate Selvon’s ‘innovative writing style’.

Men and Misogyny

There is, though, some disagreement about one of the uncomfortable aspects of The Lonely Londoners. While The Arts Desk suggests that the staging ‘beefs up the roles played by women’, The Guardian’s review says that the ‘female characters are vivid but peripheral because this is really a study of Black masculinity’. That view would be a more accurate version of the novel, which is at times discomfortingly misogynistic in its portrayal of women, who are abused, beaten and generally seen as sex objects, as the men celebrate the ‘bags of white pussy in London’ and Moses describes life as ‘Sleep, eat, hustle pussy, work.’ Agnes is regularly beaten by her husband Lewis, ‘though the poor girl don’t know what for’ until she eventually leaves after ‘he put on such a beating’. The language and the casual narration of violence against women depict a shocking view of male Caribbean attitudes. As Tolroy says, ‘you better advice that Lewis that he better stop beating Agnes. Here is not Jamaica, you know.’ It is their geographical location which outlaws Lewis’ treatment of Agnes, not human decency.

There is, though, some disagreement about one of the uncomfortable aspects of The Lonely Londoners. While The Arts Desk suggests that the staging ‘beefs up the roles played by women’, The Guardian’s review says that the ‘female characters are vivid but peripheral because this is really a study of Black masculinity’. That view would be a more accurate version of the novel, which is at times discomfortingly misogynistic in its portrayal of women, who are abused, beaten and generally seen as sex objects, as the men celebrate the ‘bags of white pussy in London’ and Moses describes life as ‘Sleep, eat, hustle pussy, work.’ Agnes is regularly beaten by her husband Lewis, ‘though the poor girl don’t know what for’ until she eventually leaves after ‘he put on such a beating’. The language and the casual narration of violence against women depict a shocking view of male Caribbean attitudes. As Tolroy says, ‘you better advice that Lewis that he better stop beating Agnes. Here is not Jamaica, you know.’ It is their geographical location which outlaws Lewis’ treatment of Agnes, not human decency.

The one variation from this picture in the novel is the matriarch, Tanty, described as ‘fantastically haughty’ in Carol Moses’ performance at the Jermyn Street Theatre in The Guardian‘s review.. In the novel, Tanty is initially presented as naïve, but develops into a figure of strength and stability in the community, even forcing the white shopkeepers to adapt their ways to her Caribbean customs. Perhaps Selvon’s portrayal of Caribbean attitudes in the 1950s is unflinchingly honest, but it would present a more rounded view of humanity if there were more figures like Tanty, or at least some female characters who fit between her powerful vitality and the cast of other objectified women.