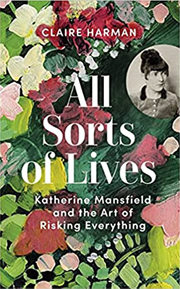

It is a century since the death of Katherine Mansfield. Timed to accord with that centenary, a new biography has been published, All Sorts of Lives by Claire Harman. This in turn has stimulated much recent consideration of Mansfield and her work in newspapers and periodicals. It is certainly a good thing to bring Mansfield’s stories to the attention of readers who may not have come across her, as she is one of the most inventive and accomplished writers of short stories there has ever been. As Claire Harman says, ‘She was on a par with Joyce, Lawrence and Woolf’. That phrase creates an equivalence between Katherine Mansfield and three pillars of twentieth century narrative, and particularly with James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, narrative experimentation.

It is a century since the death of Katherine Mansfield. Timed to accord with that centenary, a new biography has been published, All Sorts of Lives by Claire Harman. This in turn has stimulated much recent consideration of Mansfield and her work in newspapers and periodicals. It is certainly a good thing to bring Mansfield’s stories to the attention of readers who may not have come across her, as she is one of the most inventive and accomplished writers of short stories there has ever been. As Claire Harman says, ‘She was on a par with Joyce, Lawrence and Woolf’. That phrase creates an equivalence between Katherine Mansfield and three pillars of twentieth century narrative, and particularly with James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, narrative experimentation.

Katherine Mansfield was a New Zealander, though educated in England and spending most of her adult life in the UK and Europe. This puts her in an interesting position, as outlined on the Settler Colonies page of the Post Colonial Literature Course. Some of her stories are set in Europe and show a European understanding of class and gender, while the New Zealand stories sometimes show how those values are adhered to by the settlers and sometimes explore a more violent world. All sorts of lives indeed.

One of the key features of Mansfield’s writing is a shifting narrative perspective. While she usually writes in the third person, the voice of the text is sometimes detached and observant, but can suddenly occupy the perception of one of the characters, then move out again, then might move to a different character. Look how Laura’s perspective is focalised in this extract from The Garden Party, and how it characterises the youth and innocence of that perspective:

Only the tall fellow was left. He bent down, pinched a sprig of lavender, put his thumb and forefinger to his nose and snuffed up the smell. When Laura saw that gesture she forgot all about the karakas in her wonder at him caring for things like that – caring for the smell of lavender. How many men that she knew would have done such a thing? Oh, how extraordinarily nice workmen were, she thought. Why couldn’t she have workmen for her friends rather than the silly boys she danced with and who came to Sunday night supper? She would get on much better with men like these.

Here, in Frau Brechenmacher Attends a Wedding, the narrative observes the discussion between Frau Rupp and Frau Brechenmacher from outside, but gradually moves into the consciousness of Frau Brechenmacher, while maintaining the third person point of view:

“Nice time she’ll have with this one,” Frau Rupp exclaimed. “He was lodging with me last summer and I had to get rid of him. He never changed his clothes once in two months, and when I spoke to him of the smell in his room he told me he was sure it floated up from the shop. Ah, every wife has her cross. Isn’t that true, my dear?”

Frau Brechenmacher saw her husband among his colleagues at the next table. He was drinking far too much, she knew—gesticulating wildly, the saliva spluttering out of his mouth as he talked.

“Yes,” she assented, “that’s true. Girls have a lot to learn.”

Wedged in between these two fat old women, the Frau had no hope of being asked to dance. She watched the couples going round and round; she forgot her five babies and her man and felt almost like a girl again. The music sounded sad and sweet. Her roughened hands clasped and unclasped themselves in the folds of her skirt. While the music went on she was afraid to look anybody in the face, and she smiled with a little nervous tremor round the mouth.

While Virginia Woolf is usually credited with stream of consciousness narration, Mansfield was doing much the same thing at the same time. The two women were uneasy friends and rivals. Woolf once said, ‘I was jealous of her writing. The only writing I have ever been jealous of.’

While Virginia Woolf is usually credited with stream of consciousness narration, Mansfield was doing much the same thing at the same time. The two women were uneasy friends and rivals. Woolf once said, ‘I was jealous of her writing. The only writing I have ever been jealous of.’

Like Frau Brechenmacher Attends a Wedding, several of Mansfield’s stories explore the challenges of women’s place in society, while she also has spirited characters who challenge that position. Just as in her own life, sexuality is often ambiguous, particularly in a story like Bliss.

A difficult and challenging woman herself, Mansfield writes particularly well about dissatisfaction and even contempt, with characters bridling against their constraints, whether of society, family or marriage. Take Linda’s feelings in Prelude:

It had never been so plain to her as it was as this moment. There were all her feelings for him, sharp and defined, one as true as the other. And there was this other, this hatred, just as real as the rest. She could have done her feelings up in little packets and given them to Stanley. She longed to hand him that last one, for a surprise. She could see his eyes as he opened that…

She hugged her folded arms and began to laugh silently.

And in some stories, like The Woman at the Store, those feelings become violent.

Mansfield is a hugely enjoyable and very important writer. As the New Statesman review says, her work represents ‘a divide between Victorian and modern, or between a plot of cause and effect on the one hand and, on the other, the insight of short fiction – momentary, at the still point of a turning world.’

Further reading:

A consideration of the importance of Mansfield’s work in The Guardian.

An interview with Claire Harman in The Independent.

The Katherine Mansfield page on the British Library site.

A discussion of the narrative methods of The Doll’s House.