A Level results are due tomorrow. After these past two crazy years of education, I hope all students get the results they deserve and that they will be able to proceed to their future choices, whether those are in careers or further education.

Of course the British government is giving a very clear steer about what further education it deems worthwhile. At a time when France is committing 2 billion euros to the recovery and availability of culture and the arts, the UK education secretary Gavin Williamson has announced cuts to the funding of arts subjects in universities. Expressive and creative subjects such as art, design, music, drama, dance and media studies will suffer, as well as journalism – perhaps the government is fed up of being subject to scrutiny. Williamson’s reasoning is that funding should instead be concentrated on ‘the provision of high-cost, high-value subjects that support the NHS… high-cost STEM subjects [science, technology, engineering and mathematics]’

As we make tentative steps out of the pandemic, nobody will argue that funding towards support of the NHS would be misspent. Apart from, of course, the government, which is notably reluctant to award NHS staff a pay rise which might even match inflation.

Yet the dismissal of the importance of funding for creative subjects demonstrates little understanding of what the creative industries offer society, in social and cultural terms, as well as economic. One might have thought that the past two years, when the country has been desperately awaiting the reopening of cinemas, theatres, galleries, festivals and concert halls might have illustrated their importance very clearly. This is also a time when TV and film in the UK are booming, with several studios working flat out and new ones planned in Reading, and just announced, in Hertfordshire.

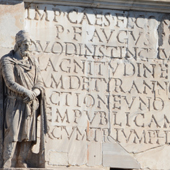

Interestingly, only two of the more prominent members of the government have STEM degrees, Alok Sharma (Applied Physics and Electronics) and Steve Baker (Aerospace Engineering). Boris Johnson, famously, has a Classics degree, which brings us to another example of the lack of governmental joined-up thinking. While pulling funding from arts and cultural degrees on the one hand, Williamson is reviving Latin in schools on the other. Williamson recognises that Latin is seen ‘as an elitist subject which is only reserved for the privileged few.’ That is true, because the National Curriculum has pushed it to the margins and it has therefore withered in most places except private schools. Williamson argues that Latin ‘can bring so many benefits to young people… Latin can help pupils with learning modern foreign languages’. That also is true, but since a modern foreign language is no longer a requirement in the National Curriculum, what is the point of learning a facilitating dead language? The teaching and learning of Latin is great – a teacher I once knew called it ‘intellectual gymnastics’ – and is hugely valuable for etymology as well as the wide cultural reference pool. But the government’s sudden selection of Latin in this way is absurd, as Michael Rosen, in his normal pithy way, points out.

Interestingly, only two of the more prominent members of the government have STEM degrees, Alok Sharma (Applied Physics and Electronics) and Steve Baker (Aerospace Engineering). Boris Johnson, famously, has a Classics degree, which brings us to another example of the lack of governmental joined-up thinking. While pulling funding from arts and cultural degrees on the one hand, Williamson is reviving Latin in schools on the other. Williamson recognises that Latin is seen ‘as an elitist subject which is only reserved for the privileged few.’ That is true, because the National Curriculum has pushed it to the margins and it has therefore withered in most places except private schools. Williamson argues that Latin ‘can bring so many benefits to young people… Latin can help pupils with learning modern foreign languages’. That also is true, but since a modern foreign language is no longer a requirement in the National Curriculum, what is the point of learning a facilitating dead language? The teaching and learning of Latin is great – a teacher I once knew called it ‘intellectual gymnastics’ – and is hugely valuable for etymology as well as the wide cultural reference pool. But the government’s sudden selection of Latin in this way is absurd, as Michael Rosen, in his normal pithy way, points out.