As promised, we are now going to have some students’ views on a range of more contemporary literature. We have English novels, American novels and a work in translation from German. Translation itself is a whole topic we could get into some day. Every reading is an act of translation, according to George Steiner.

Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch and The Secret History

Apart from Tartt’s plot being amazing and the characters very well developed, there were a few similarities that stuck out to me from one of Tartt’s previous novels, The Secret History. Both books focus on action (and the build-up) and developing relationships. However, the order in which this is done in the two novels is inversed; the action came more towards the end of The Goldfinch, after Boris and Theo are reunited, while it is at the beginning of The Secret History, up until the point of the murder. The reason lies in that the motives which propel the action sequences of the novels rest upon the relationships between the characters. In The Goldfinch, Theo leaves his engagement party because, and only because, of his relationship with Boris. The trauma which both characters go through, as described in the early part of the book, bonds them together in such a way that Theo trusts Boris implicitly (I would argue they are in love with each other), despite the many years they’ve spent apart and his attempts to rebuild his life for Kitsey. Yet, in The Secret History, Richard’s involvement with the murder and the rest of the group comes about because of his lack of knowledge of the true workings of their relationships. Henry manipulates him, praising his intelligence, ‘You’re just as smart as I thought you were’, and appealing to Richard’s ‘morbid longing for the picturesque’ to rope him into his scheme. After the murder and the search, the group comes to understand that the possibility of them going to prison rests on the fact that they don’t trust each other. The relationships that form in Book II sustain them for a lot longer, but trust forms too late and it tears them apart.

Apart from Tartt’s plot being amazing and the characters very well developed, there were a few similarities that stuck out to me from one of Tartt’s previous novels, The Secret History. Both books focus on action (and the build-up) and developing relationships. However, the order in which this is done in the two novels is inversed; the action came more towards the end of The Goldfinch, after Boris and Theo are reunited, while it is at the beginning of The Secret History, up until the point of the murder. The reason lies in that the motives which propel the action sequences of the novels rest upon the relationships between the characters. In The Goldfinch, Theo leaves his engagement party because, and only because, of his relationship with Boris. The trauma which both characters go through, as described in the early part of the book, bonds them together in such a way that Theo trusts Boris implicitly (I would argue they are in love with each other), despite the many years they’ve spent apart and his attempts to rebuild his life for Kitsey. Yet, in The Secret History, Richard’s involvement with the murder and the rest of the group comes about because of his lack of knowledge of the true workings of their relationships. Henry manipulates him, praising his intelligence, ‘You’re just as smart as I thought you were’, and appealing to Richard’s ‘morbid longing for the picturesque’ to rope him into his scheme. After the murder and the search, the group comes to understand that the possibility of them going to prison rests on the fact that they don’t trust each other. The relationships that form in Book II sustain them for a lot longer, but trust forms too late and it tears them apart.

Furthermore, both narrators (first-person men) are distinctly unreliable while being in love with an unattainable love interest. Both are fuelled by alcohol and drugs and these factors contribute to the elements of mystery within the novels and the lack of understanding the two narrators truly have of their own situations.

Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin

With gun ownership in the United States as widespread as ever, We Need to Talk about Kevin produces a new perspective on the hotly debated topic, the perspective of a grieving parent, the parent of the school shooter.

With gun ownership in the United States as widespread as ever, We Need to Talk about Kevin produces a new perspective on the hotly debated topic, the perspective of a grieving parent, the parent of the school shooter.

Shriver’s novel is written as interchange of letters between Eva Khatchadourian and her husband, in which she details her life and the life of her son, culminating in his arrest. We learn that Eva had not wanted a son and didn’t want to be plucked away from her bohemian lifestyle of running a travel agency. When she finally does embrace motherhood, she does so in a perfunctory manner, and Kevin seems to dislike her from birth.

As mother and son grow older, conflict arises between them over Kevin’s psychopathic behaviour. His lack of empathy and cruelty towards others frightens Eva, while everyone else, including his father, Franklin, is won over by Kevin’s apparent normality.

This story is woven in with scenes from after the shooting, ‘Thursday’ as Eva refers to it, and the detrimental toll the massacre has taken on her life as she is forced to give up her comfortable middle-class lifestyle, in exchange for that of a pariah.

The book sensitively examines the impact of gun violence, as well as parenthood, shown by Kevin’s cold attitude to human life and his ruthless dismissal of any potential relationships. But the question that remained long after I had put the novel down and continued to perturb my mind for the following weeks was about responsibility. Was it Eva’s ineptitude and indifference to motherhood that resulted in Kevin’s indifference to life? Or are some people born evil, born with no inherent wants or needs and therefore display a complete absence of remorse?

Ian McEwan’s The Cement Garden

When picking this book up, I was completely ignorant of the dark and disturbing content of the novel. However, it didn’t take more than a few pages for the subject of incest to creep in. McEwan takes up the mission to write it as a more romantic device and is able to craft it in such a way that it is perversely understandable, although no less nauseating. The driving narrative of the book focuses on four children who have decided to bury their mother in the cellar to avoid social care. From there McEwan might well have taken inspiration from Golding’s Lord of the Flies to show how children left to the own devices in leadership roles can become so wrong and disturbing. Interestingly, McEwan’s novel does not present any character you can really resonate with and they all seem to be written in quite a hollow manner. This yet again adds to the unsettling and quite frightening atmosphere, which certainly backs up McEwan’s nickname as ‘Ian Macabre.’

When picking this book up, I was completely ignorant of the dark and disturbing content of the novel. However, it didn’t take more than a few pages for the subject of incest to creep in. McEwan takes up the mission to write it as a more romantic device and is able to craft it in such a way that it is perversely understandable, although no less nauseating. The driving narrative of the book focuses on four children who have decided to bury their mother in the cellar to avoid social care. From there McEwan might well have taken inspiration from Golding’s Lord of the Flies to show how children left to the own devices in leadership roles can become so wrong and disturbing. Interestingly, McEwan’s novel does not present any character you can really resonate with and they all seem to be written in quite a hollow manner. This yet again adds to the unsettling and quite frightening atmosphere, which certainly backs up McEwan’s nickname as ‘Ian Macabre.’

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World

I read Brave New World on the recommendation of a family friend and it has been on of the books on my reading list for a while, with a reputation for being accessible yet profound. After struggling to pin down the plot and characters in the first few chapters (not in the least helped by Chapter 3’s intolerable structure), I enjoyed the novel. Huxley’s investigation of the ethics of an ideal society struck a chord, and made me wonder how much further our own society could go down its current path. The ironic use of ‘The Savage’ resonated as well; Huxley clearly believes in the Savage’s ideals despite his flawed character (even if he does turn from an entirely uneducated man to an intellectual within a few weeks!) The ending seems a little rushed to me, but overall I enjoyed the book, missing the novel with a non-fiction book, Sam Willis and James Daybell’s A History of the Unexpected. I enjoyed this too, with the chapters on the history of dust and the itch coming to mind immediately. The intertwining histories also piqued my interest, although the concluding few sentences of each chapter to facilitate these transitions feels a little forced.

I read Brave New World on the recommendation of a family friend and it has been on of the books on my reading list for a while, with a reputation for being accessible yet profound. After struggling to pin down the plot and characters in the first few chapters (not in the least helped by Chapter 3’s intolerable structure), I enjoyed the novel. Huxley’s investigation of the ethics of an ideal society struck a chord, and made me wonder how much further our own society could go down its current path. The ironic use of ‘The Savage’ resonated as well; Huxley clearly believes in the Savage’s ideals despite his flawed character (even if he does turn from an entirely uneducated man to an intellectual within a few weeks!) The ending seems a little rushed to me, but overall I enjoyed the book, missing the novel with a non-fiction book, Sam Willis and James Daybell’s A History of the Unexpected. I enjoyed this too, with the chapters on the history of dust and the itch coming to mind immediately. The intertwining histories also piqued my interest, although the concluding few sentences of each chapter to facilitate these transitions feels a little forced.

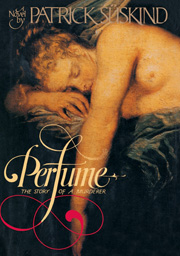

Patrick Süskind’s Perfume

Perfume is a bizarre yet captivating novel. I won’t spoil the plot, but an outstanding feature of the novel is that it is, appropriate to its title, depicted in an olfactory way rather than visual. This is due to the protagonist’s remarkable abilities in this field. I found the intertwining sentiments of compulsion and repulsion striking, Süskind persuading the reader to sympathise with the protagonist Jean-Baptiste Grenouille despite that repulsion. I first decided to explore this novel after digging deeply into some interviews with Kurt Cobain; he mentioned it being a permanent pocket-filler for him.

Perfume is a bizarre yet captivating novel. I won’t spoil the plot, but an outstanding feature of the novel is that it is, appropriate to its title, depicted in an olfactory way rather than visual. This is due to the protagonist’s remarkable abilities in this field. I found the intertwining sentiments of compulsion and repulsion striking, Süskind persuading the reader to sympathise with the protagonist Jean-Baptiste Grenouille despite that repulsion. I first decided to explore this novel after digging deeply into some interviews with Kurt Cobain; he mentioned it being a permanent pocket-filler for him.

Amanda Gorman

In other news, wasn’t it good to see poetry at centre stage and grabbing the discussion at Joe Biden’s inauguration ceremony?