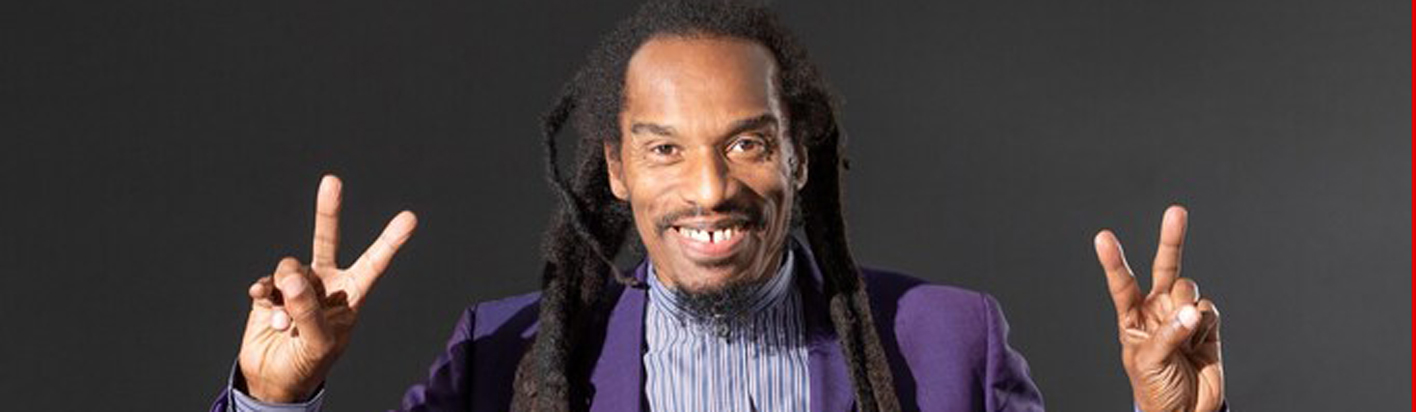

It was saddening to hear of Benjamin Zephaniah’s untimely death last week. A dyslexic Rastafarian with limited formal education and several brushes with the police is an unlikely literary hero, but that very history has made him such a powerful and inspirational figure.

I had two unexpected encounters with Zephaniah on the radio. The first was in 1988 when I didn’t know much about him, but happened to switch on and found myself listening to a compelling and unusual radio play. I hadn’t intended to listen, but was entranced and stayed until the end, and discovered it was Hurricane Dub, by Benjamin Zephaniah. Several years later, I happened to switch on the radio and found that it was broadcasting from the Cambridge Folk Festival. A group called The Imagined Village had invited writers to reinvent English folk songs, and they played a version of ‘Tam Lyn’, written and voiced by Zephaniah.

The original tale, versions of which are found all around Europe, tells of how Tam Lyn is rescued by his true love from the a witch-like figure who has him in a spell. To accomplish this, she must hold on to him faithfully while the witch causes him to transform repeatedly into different creatures. She succeeds by hanging on until he returns to his original shape. ‘Make love, not war; this is how we do it./ Make love not war; this is how we flow’ is the refrain of Zephaniah’s version, and Tam Lyn is a ‘war refugee’ who has entered the country illegally. The transformations are how he is characterised in court – she holds on until he is granted leave to remain and their child becomes a ‘club DJ’.

With the debate about the new laws trying to deport refugees and migrants to Rwanda, this version from 2008 is uncannily topical today. I often used a recording of the live performance in classes about the literature of immigration and hybridity, seen in musical form, as a traditional English folk tale is not just transformed in the lyrics, but by a band which consciously pulls together the musical instruments and style of immigrant communities, to create a vibrant, joyful mix. Happily, you can watch it here:

Zephaniah was warm-hearted but passionate with clear political convictions. Having been an underdog in society, he always fought for the underdog and positioned himself calmly and clearly against any form of cruelty and oppression. See him on Question Time calmly dismantling Boris Johnson.

Zephaniah was warm-hearted but passionate with clear political convictions. Having been an underdog in society, he always fought for the underdog and positioned himself calmly and clearly against any form of cruelty and oppression. See him on Question Time calmly dismantling Boris Johnson.

See him here talking about why he rejected the offer of an MBE (Member of the British Empire), with such clarity and conviction he persuades the interviewer to hand back his own:

There have been many warm tributes and here are a few:

The BBC, The Guardian. The Independent.

There is also a great article here from Hugh Muir, which says:

I think there was a sort of genius to him; he carried an iron fist in a velvet glove. I can always see him smiling, even as he was challenging some injustice or dismantling a racist, illiberal argument. He had fire, but not the visible anger the right seizes upon and weaponises.

And of course if you visit the Poetry Archive, you can not only read a further tribute, but hear Zephaniah reciting some of his poems.

You could also read his autobiography, The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah.

You could also read his autobiography, The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah.

Coming to reading and writing late, and always cautious about received ideas, he was also cautious about received language. We wanted to find a written expression which was his, reflected his experience and his voice. You can see this at work in this poem:

Speak

You teach meAir Pilots language

De language of

American Presidents

A Royal Family

Of a green unpleasant land.

It is

Authorised

Approved

Recycled

At your service.

I speak widda bloody tongue,

Wid Nubian tones

Fe me riddims

Wid built in vibes.

Yu dance.