It’s happening again, of course. The latest dying-fish twitch of the UK government is to resume its attack on arts education. Education Secretary Gillian Keegan has just announced not only cuts in funding to creative arts courses, but also to a scheme which aims to widen access to higher education for students from less advantaged backgrounds. Levelling up, anyone?

The Arts’ Economic Value

The Arts’ Economic Value

This makes no sense on any level. As the Arts Council UK has shown, the arts and culture industries contribute £10.6 billion to the UK economy. You would have thought that those figures at least would appeal to a monetary value-obsessed government. The Arts Council also points out that arts and culture, through theatres, museums, galleries and libraries, provide the civic pride and sense of place which make communities thrive. However, there have been many signs that the current government is not really interested in civic pride outside London or in tackling social injustice. Equally, the UK’s creative industries are renowned worldwide and are an important export – though of course the exchange of culture with Europe has deep deeply hampered by Brexit.

Even the House of Lords is more alert than the government in the House of Commons. One of their reports points out that film and TV turns over £20.8 billion and employs 283,000 people. For publishing, it’s £11.6 billion and 209,000 people, and for music and performance it’s £11.2 billion and 283,000 people for example. Yet the government seems to think that these activities and industries are not worth investment.

Applying the Science

Applying the Science

We have data on what artistic companies spend and what their income is, but harder to pin down than the raw economics of the arts is the value to the people of a community.

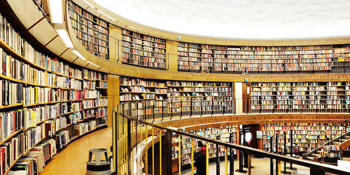

Visiting a free museum, walking past a historic building, going to a theatre: these activities bring enjoyment to many people, and are often supported by public funding. The presence of historic buildings and cultural facilities can also be important to local communities even if they do not directly use or visit them.

This research does a remarkable job of placing a monetary value on people’s value of the cultural assets of their communities.

That is still about the money, though. Surely it’s impossible to quantify the value to our feelings, our sense of satisfaction, our well-being? Apparently not. Neuroscientists have taken on that problem and shown that ‘Empirical research on art appreciation can … be used to show that engagement with art has specific social and personal value, the cultivation of which is important to us as individuals, and as communities.’

As Charlotte Higgins in The Guardian points out, visits to museums, theatre performances, concerts and libraries are fundamental to how communities see and shape themselves and need to be valued:

As Charlotte Higgins in The Guardian points out, visits to museums, theatre performances, concerts and libraries are fundamental to how communities see and shape themselves and need to be valued:

It is about offering people ideas beyond their immediate experience – ideas that can bring delight, hope and joy, but also spark individuals’ ambitions, or suggest possibilities beyond their immediate horizon.

The arts are, of course, the way humanity has been seeing itself and shaping itself to its changing environment since the beginnings of time.

Lessons from Hollywood

Despite the research to measure the economic impact of culture, perhaps this is the wrong approach. Sam Ladkin, senior lecturer in creative and critical writing at the University of Sussex, argues that it is:

Art is a victim of audit culture … What’s wrong with how we judge the arts is the fact that we believe something is justifiable only if it can be translated into money.

This comment is included in this piece from Harper’s Bazaar, which considers the low pay and lack of stability for many people who work in the arts. The Hollywood actors’ and writers’ strikes for fair pay and recognition made it clear that for every millionaire celebrity A-lister, there are hundreds of workers who struggle to make a proper living in the same industry.

What fascinates about these moments in Hollywood is how far reaching their implications are. The questions raised by the strike action, and the vast scale of them, are profoundly resonant to the arts in general and how much we value them – or don’t. Because if we no longer ascribe any intrinsic worth to the people who have meticulously crafted what we read, watch and enjoy, what does that say about how highly we think of the arts in society?