An actor’s job is to pretend to be someone else. An audience applauds them for effacing themselves in order to portray a character who is not themselves, using voice and movement. It is an art of imitation and some actors engage in lengthy and intense periods of research in order to understand their characters fully – their background, their attitudes, their physicality, their vocal mannerisms – in order to portray them authentically on the stage or screen.

The Discrediting of Blackface

That view of the actor’s art and skill has become challenged in recent years, with the vexed question of the ethics of casting decisions – who should be allowed to play who?

In 1965 the revered actor Lawrence Olivier was nominated for an Oscar for his portrayal of Shakespeare’s Othello, a filmed adaptation of the production at London’s National Theatre. Being the sixties, he played the role in blackface, which at the time drew no comment or opprobrium. I saw a production of Othello in a repertory theatre sometime in the seventies, and again the main role in blackface was not deemed controversial. There is an interesting article on the development of productions of Othello here.

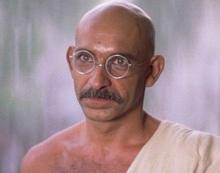

There was some disquiet about the casting of Alec Guinness as Godbole in David Lean’s A Passage to India in 1984, certainly playing the part with some heavy make-up. However, times have moved on – such an idea now would be utterly unthinkable, though interestingly there was some debate about the casting of English actor Ben Kingsley as Mahatma Gandhi in Richard Attenborough’s 1982 film Gandhi, despite Kingsley being the son of a Gujarati father (his birth name was Krishna Pandit Bhanji).

There was some disquiet about the casting of Alec Guinness as Godbole in David Lean’s A Passage to India in 1984, certainly playing the part with some heavy make-up. However, times have moved on – such an idea now would be utterly unthinkable, though interestingly there was some debate about the casting of English actor Ben Kingsley as Mahatma Gandhi in Richard Attenborough’s 1982 film Gandhi, despite Kingsley being the son of a Gujarati father (his birth name was Krishna Pandit Bhanji).

The Jewish Question

More recently, the same kind of questions have been asked about Jewish roles. These are more difficult when the role is in itself contentious, like Shakespeare’s Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. The notorious moneylender insistent on claiming his ‘pound of flesh’ was humanised and played with considerable sympathy by Al Pacino in Michael Radford’s 2004 film, though Pacino is Italian-American. The play was given a much more radical treatment in Brigid Lamour’s stage adaptation, which placed the action in the east London of the 1930s, with the rise of Oswald Moseley’s racist Blackshirts. In this production, Shylock was played by Tracy-Ann Oberman, as a matriarch and pawnbroker. Oberman, as a Jewish actor, has said the production is ‘the project of my life, the moment where my politics, my family history, my activism and my art has come together in a beautiful moment.’ Her idea is not to cancel the play, but to reclaim it. As she says,

It’s deeply uncomfortable: either you pity Shylock, or you hate him or you find him a mocked character and I don’t know which is worse. I wanted to reclaim this play. It is important to me that it is understood as antisemitic.

By changing Shylock’s gender and setting the play in a more recent time of avowed antisemitism, the treatment of Shlyock is made more shocking, and the production was touring last autumn and is due to return this year, at a time when anti-Semitic incidents are on the rise as a response to the Israel/Gaza conflict.

By changing Shylock’s gender and setting the play in a more recent time of avowed antisemitism, the treatment of Shlyock is made more shocking, and the production was touring last autumn and is due to return this year, at a time when anti-Semitic incidents are on the rise as a response to the Israel/Gaza conflict.

It is quite striking for a Jewish actor to take on a role often perceived as anti-Semitic, but the question now arises whether only Jewish actors should play Jewish roles. Maureen Lipman criticised the casting of Helen Mirren as Golda Meir in Guy Nattiv’s biopic Golda and there has been much criticism of Bradley Cooper’s performance as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro last year, with particular reference to his prosthetic nose. So should only Jews play Jews? Here’s an interesting take from The Jewish Chronicle.

Disability

The latest are for these debates is disability, particularly prompted by the announcement of the Globe’s new season, which includes a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III. In another gender-swap, artistic director Michelle Terry will take the title role of Shakespeare’s villainous scheming king. It is interesting that cross-gender performances are now commonplace and largely go unchallenged; the issue here is that Terry is able-bodied, while Richard describes himself in the play as ‘deformed’. Historians have shown that he suffered from scoliosis, which is an abnormal curvature of the spine.

The latest are for these debates is disability, particularly prompted by the announcement of the Globe’s new season, which includes a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III. In another gender-swap, artistic director Michelle Terry will take the title role of Shakespeare’s villainous scheming king. It is interesting that cross-gender performances are now commonplace and largely go unchallenged; the issue here is that Terry is able-bodied, while Richard describes himself in the play as ‘deformed’. Historians have shown that he suffered from scoliosis, which is an abnormal curvature of the spine.

As reported here in The Independent, disabled actors are upset that an able-bodied actor is taking the role of perhaps the ‘most iconic disabled character’, suggesting that it should be played by a performer with a disability. A letter of protest from the Disabled Artists Alliance has said,

It is offensive and distasteful for Richard to be portrayed by someone outside the community. It reduces disability down to a disguise and physical act, rather than a true grounded understanding of what disability means.

Read more about the debate on the Disability News Service here.

One can understand the views, though Terry and the Globe are sticking to their guns. If we applied the rule of Only Disabled Play Disabled, we would not have had Antony Sher’s mesmeric turn as Richard (left) in 1984. Nor would audiences have seen John Hurt’s 1982 performance in The Elephant Man. Should we view those performances now in the same light as Olivier’s Othello? And what about Daniel Day-Lewis’ acclaimed and award-winning performance of Christy Brown, the Irish artist with cerebral palsy, in My Left Foot in 1989? Read this account of how seriously he took the role.

One can understand the views, though Terry and the Globe are sticking to their guns. If we applied the rule of Only Disabled Play Disabled, we would not have had Antony Sher’s mesmeric turn as Richard (left) in 1984. Nor would audiences have seen John Hurt’s 1982 performance in The Elephant Man. Should we view those performances now in the same light as Olivier’s Othello? And what about Daniel Day-Lewis’ acclaimed and award-winning performance of Christy Brown, the Irish artist with cerebral palsy, in My Left Foot in 1989? Read this account of how seriously he took the role.

Sexuality

And of course there is the question of whether only gay actors should play gay roles. Should gay actors play straight roles? It’s a thorny debate, and there is much to recommend the idea that minority or oppressed groups are given their chance to shine. However, the more exclusionary casting becomes, the more typecasting we will see and audiences will see fewer actors whose job is to pretend to be someone else.