Andrew Scott’s performance as Ripley in the new Netflix series based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel has been making a lot of news. The Talented Mr Ripley was published in 1955 and was an immediate hit. It was nominated for the Edgar Allen Poe Award and won the Grand Prix de Litérature Policière as the best international crime novel in 1957. Anthony Minghella directed Matt Damon in the role in a film in 1999, a sumptuous and compelling version. Yet here it is again, over eight episodes on Netflix. Rather than the warm sunshine glow of the Minghella version, we have a Ripley noir, artfully shot throughout in black and white.

Andrew Scott’s performance as Ripley in the new Netflix series based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel has been making a lot of news. The Talented Mr Ripley was published in 1955 and was an immediate hit. It was nominated for the Edgar Allen Poe Award and won the Grand Prix de Litérature Policière as the best international crime novel in 1957. Anthony Minghella directed Matt Damon in the role in a film in 1999, a sumptuous and compelling version. Yet here it is again, over eight episodes on Netflix. Rather than the warm sunshine glow of the Minghella version, we have a Ripley noir, artfully shot throughout in black and white.

Reviews of the Series

Comments on Scott’s performance in the central role have been varied as you will see here, some praising his sinuous dangerous charm while others have been less struck and some have been worried about his age. Here are some reviews to consider. The Guardian views Scott as ‘absolutely spellbinding, while ‘every ounce of his talent, ineffable charm and lightly reptilian hotness [is] on display’. Tatler too is a fan, claiming that the adaptation is ‘is total artistry: dark, depressive and brooding’ and ‘a transfixing watch’.

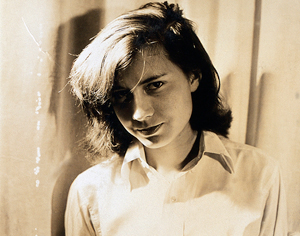

Highsmith’s Dark Side

Highsmith’s Dark Side

Underneath the charm, of course, Tom Ripley is a pretty disturbing character. Highsmith went on to write four further Ripley novels and all her novels explore the dark side of human nature. As this feature on the writer points out,

Highsmith’s novels are filled with characters who, like Ripley, would look entirely normal if you passed them in the street, yet are consumed by dark impulses, horrible secrets, and the fear of being found out.

As the article explains, Highsmith herself had a pretty dark side. Keeping pet snails in your handbag is one thing, but her manipulative relationships were questionable and her racism deeply offensive. As the writer points out,

Much like her best characters, she remains an impossible, horrible conundrum, enthralling and repellent at the same time.

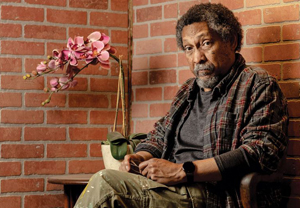

Percival Everett’s Charm

Everett, who we featured a year ago, couldn’t be more different from Highsmith. When he was first appointed by the University of Southern California, a faculty member saw his name on the list and said, ‘The last thing we need is another 50-year-old Brit,’ only to be told by the receptionist that the newest professor was in fact a ‘black cowboy’.

Everett, who we featured a year ago, couldn’t be more different from Highsmith. When he was first appointed by the University of Southern California, a faculty member saw his name on the list and said, ‘The last thing we need is another 50-year-old Brit,’ only to be told by the receptionist that the newest professor was in fact a ‘black cowboy’.

That anecdote appears in this feature on Everett, which focuses in particular in his most recent novel James. An engaging picture emerges of Everett, a man impatient with glitz and glamour and happy to encounter different views of his work. His novel Erasure is the basis of the recent film American Fiction and he is happy to see the film take its own course with his material. As the headline indicates, he would be fascinated rather than offended by a stinking review and has this comment on his university post:

It’s why I like teaching – because I get to go out into the world and be reminded that there are other people thinking different thoughts.

Retelling Huckleberry Finn

His new novel James is a reworking of Mark Twain’s American classic The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, turning the narration around from Huck to Jim. Not only is Jim given his full, formal name, James, but proves to be an articulate and thoughtful narrator. The phonetically-expressed black vernacular which Twain employs in his novel is shown to be a front constructed by the slaves to reassure the white population of its control and superiority.

His new novel James is a reworking of Mark Twain’s American classic The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, turning the narration around from Huck to Jim. Not only is Jim given his full, formal name, James, but proves to be an articulate and thoughtful narrator. The phonetically-expressed black vernacular which Twain employs in his novel is shown to be a front constructed by the slaves to reassure the white population of its control and superiority.

Although The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a controversial novel, particularly in America where it is banned by some school boards because of the frequency of the n-word, Everett praises Twain’s text and its depiction of the young Huck:

He’s got this moral conundrum: ‘He belongs to someone and I’m doing something illegal by helping him run, but he’s my friend and a person, and he shouldn’t be a slave.’ There’s nothing more American.

Huck’s own development on the raft journey down the Mississippi with Jim is crucial to the novel, encapsulated by the scene where he feels he is willing to be sent to hell because he refuses to surrender Jim – he rejects the rules of his society in favour of his own understanding and relationship.

By changing the perspective, Everett peels back the assumptions which even Twain had, giving control of the narrative to Twain’s important but secondary character.

Literary Guides

Everett likes teaching, and so does Carol Atherton, whose recent book Reading Lessons shows how even classic literary texts can speak to students now with relevance and insight. Read about it here.