Playing with Narrative

We think of the modern novel as the place for narrative experiment, but in fact such experimentation has been going on for as long as there have been novels.

Once upon a time, you knew where you were with a narrator. The narrator was the informed voice of the novel, leading you knowledgeably through the story. Occasionally, the narrator took part in the story too, telling it from the inside, in the first person.

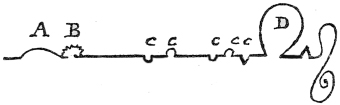

Of course, while this tidy history might be true of our reading progression from infancy, it’s far from true in the progression of the novel itself. From the outset, novelists have experimented with the form that narrative might take. It has not been a linear, ordered progression. In fact, you could say it has been something like this:

Early Experimentation

This is, perhaps, one of the more unusual literary quotations you are likely to come across. It is a line, quite literally, from Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, an astonishingly modern, experimental work, especially considering it was first published in 1759. It is a big, meandering book, and at one point the eponymous narrator stops to take stock of his narrative direction, charting the progress of the preceding sections of the novel with diagrams. Of the diagram above, he says that the c c c c c “are nothing but parentheses”, while A B and D represent his “own transgressions” from the “tolerable straight line” of the story. He laments his lack of rectitude and determines that the narrative line of the next section will be ruler-straight. He fails, of course, and that’s the point. The book is about the delight in narrative itself, and Sterne constantly plays with how a story might be told, varying chapter lengths from substantial to nothing, leaving blank pages, filling pages with marbling, constructing lines out of nothing but punctuation, and so on. And to cap it all, the garrulous narrator proves to have told us the biggest shaggy dog story of the lot.

Moll Flanders – Apparent Autobiography

The extent of Sterne’s experimentation is unusual, but the way that the narrator impresses themself on the narrative form is clear. It is equally clear, but in a very different way, in Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel, Moll Flanders. This novel purports to be the autobiography of a woman with a troubled history of destitution, criminality and sexual exploits. Here the voice of the narrator is almost audible:

The extent of Sterne’s experimentation is unusual, but the way that the narrator impresses themself on the narrative form is clear. It is equally clear, but in a very different way, in Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel, Moll Flanders. This novel purports to be the autobiography of a woman with a troubled history of destitution, criminality and sexual exploits. Here the voice of the narrator is almost audible:

Away goes the old lady to her daughters and tells them the whole story, just as I had told it her; and they were surprised at it, you may be sure, as I believed they would be. One said she could never have thought it; another said Robin was a fool; a third said she would not believe a word of it, and she would warrant that Robin would tell the story another way.

The sense of immediacy here is created by a move into the present tense and the conversational style is continued – it as if the reader is being chattily addressed by Moll, with such phrases as “you may be sure”. The three daughters’ responses demonstrate the range of responses possible to any story, while the third daughter is astute, recognising that the narrator of any tale has a crucial role in shaping it and guiding interpretation. This conversational style, almost taking the ear of the reader, is appropriate for a novel which is confessional, which involves the sharing of intimate experiences.

Jane Austen

Compare this with the cool narration of Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice (1813). Being told you should have no interest in a man, who has previously proposed to you, because your position in society is not worthy enough, by the man’s aunt, is certainly an event of high emotion. Austen’s narrator steps back, though, and gives us dialogue:

Compare this with the cool narration of Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice (1813). Being told you should have no interest in a man, who has previously proposed to you, because your position in society is not worthy enough, by the man’s aunt, is certainly an event of high emotion. Austen’s narrator steps back, though, and gives us dialogue:

‘Let me be rightly understood. This match, to which you have the presumption to aspire, can never take place. No, never. Mr Darcy is engaged to my daughter. Now what have you to say?’

‘Only this; that if he is so, you can have no reason to suppose he will make an offer to me.’

Lady Catherine hesitated a moment, and then replied,

‘The engagement between them is of a peculiar kind. From their infancy, they have been intended for each other.’

The narrative does not direct our responses; it remains coolly detached and we make judgements by noting the tone of the dialogue. The peremptory vocabulary and sentence structure of Lady Catherine is repellent and the reader is left to admire the dignity of Elizabeth’s measured reply. It is left to the reader to judge the gap between the peremptoriness and the dignity in order to imagine the emotional turmoil in Elizabeth’s mind. Even the next chapter, where the narrative focuses on Elizabeth’s mind, is observant rather than emotional, referring to ‘The discomposure of spirits, which this extraordinary visit threw Elizabeth into’. Though a third person narrative, it is one which follows Elizabeth’s story, and we can perhaps see here that the steady control of emotion in the narrative is a feature of Elizabeth herself. Jane Austen creates a narrator who mirrors, in many ways, the characteristics of her heroine.

Jane Eyre

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) is the narrator of her own story and remains very conscious of that role, addressing the ‘Reader’ throughout, directing observations and raising questions. In the following example, the narrator sets out the planning and shaping of the narrative, accentuating the artifice and the relationship between the narrator and reader.

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) is the narrator of her own story and remains very conscious of that role, addressing the ‘Reader’ throughout, directing observations and raising questions. In the following example, the narrator sets out the planning and shaping of the narrative, accentuating the artifice and the relationship between the narrator and reader.

A new chapter in a novel is something like a new scene in a play; and when I draw up the curtain this time, reader, you must fancy you see a room in the George Inn at Millcote, with such large figured papering on the walls as inn rooms have; such a carpet, such furniture, such ornaments on the mantelpiece, such prints, including a portrait of George the Third, and another of the Prince of Wales, and a representation of the death of Wolfe.

The direct references to the “chapter” and the “novel” lay bare the construction of the story. At the same time, the responsibility and creativity of the reader is invoked. The room at the George is not directly described – it is left to the reader’s “fancy” to imagine the “large figured papering” and the portraits “on the walls”. This is a neat sleight of hand, as the room’s décor has, in fact, been described by the narrator. Here the reader is in the narrator’s confidence; we are clearly and directly being told a story. The reader is guided and unequivocally directed.

Shifting Narrators in Wuthering Heights

In Wuthering Heights, however, Charlotte Brontë’s sister Emily takes a very different route, piecing together a story from different narrative perspectives, shifting between the pompous Lockwood and the garrulous Nelly Dean. The reader has to work out their own version of the story from what Lockwood tells, what Nelly tells, and what Lockwood tells us that Nelly tells. Emily Brontë makes the real heart of the story elusive and the manner of the telling as important as the tale that is told.

In Wuthering Heights, however, Charlotte Brontë’s sister Emily takes a very different route, piecing together a story from different narrative perspectives, shifting between the pompous Lockwood and the garrulous Nelly Dean. The reader has to work out their own version of the story from what Lockwood tells, what Nelly tells, and what Lockwood tells us that Nelly tells. Emily Brontë makes the real heart of the story elusive and the manner of the telling as important as the tale that is told.

One of the features of this dual narration is the subtle shift between storytellers. Take this section from the final stages of the novel:

Yet, still, I don’t like being out in the dark now; and I don’t like being left by myself in this grim house: I cannot help it; I shall be glad when they leave it, and shift to the Grange.

“They are going to the Grange, then,” I said.

“Yes,” answered Mrs Dean, “as soon as they are married, and that will be on New Year’s Day.”

The “I” of the first paragraph here is Nelly Dean, coming to the close of her narration, but after the intervention of the second “I” after the dialogue, which is Lockwood, Nelly is referred to in the third person, as “Mrs Dean”. By strict grammatical rules, this is incorrect – the first narrative section should be in speech marks too, to indicate an exchange of speakers. The first paragraph’s and the dialogue’s “I”, both outside the speech marks, should refer to the same character. However, Emily Brontë dispenses with the formal precise rules of grammar to create this fluid transfer from narrator to narrator, from story to story. The effect of this is to move the reader along a kind of narrative stream, which, sometimes disconcertingly, shifts course as it rushes onwards.

The narrators of Moll Flanders, Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights are part of the stories they tell, and therefore each of them, even with the certainty and apparent honesty of Jane Eyre, is to some extent fallible. The narrators are characters themselves; they have a point of view, a reason for narrating. The stories told are their versions, not a definitive tale. Tristram Shandy’s digressions make this narrator intervention abundantly clear. But we can also see that even an apparently authoritative third person narration in Austen’s novel is infused with features of character. Indeed, “Robin would tell the story another way”; novelists’ experiments with narration have always demonstrated this.

Further reading:

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice

Charlotte Brontë: Jane Eyre

Emily Brontë: Wuthering Heights

Daniel Defoe: Moll Flanders

Laurence Sterne: The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy

A version of this article first appeared in emag issue 39, February 2008