If you have ever been on the London Underground, at least since 1986, you’ll have seen them. Tucked up on the panels above the windows of the trains, squeezed between adverts for accounting software and wellness supplements, a little bit of culture. Poems. On the underground.

If you have ever been on the London Underground, at least since 1986, you’ll have seen them. Tucked up on the panels above the windows of the trains, squeezed between adverts for accounting software and wellness supplements, a little bit of culture. Poems. On the underground.

The tube might seem an odd place to put poems, but the idea was always to remove poems from books and libraries and put them straight into daily life, juxtaposing moments of observation with the daily commute.

The organisation behind the project claims that:

Poetry speaks to our common humanity and our shared values, transforming the simplest of poems into a powerful catalyst for dialogue, thought and peace.

That’s quite a statement. Jessie Pope and Wilfred Owen might have had a common humanity, but clearly not shared values. Would Philip Larkin and Benjamin Zephaniah have seen quite eye to eye?

While we might quibble with that statement, it’s hard to disagree with the organisation’s statement that ‘Poems on the Underground has become one of Britain’s most successful public art projects’. Started as an experiment in the 1980s, it has run continuously ever since, pasting up verses by world-famous and prize-winning poets alongside work by new and lesser-known writers. It has been such a success that the idea has been copied in cities across the world, including Shanghai and New York.

Back to Books

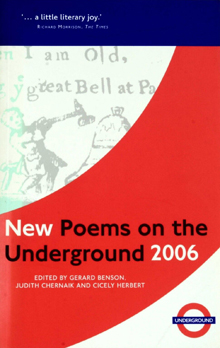

As an ironic sign of the scheme’s success, the poems have reverted from the walls of tube trains and back into books. They are still in the trains of course, but 100 Poems on the Underground was published in 1991 and different versions and collections have been published frequently since. These books sell well, and one must assume that a good number of the purchasers are people who have been inspired by reading poems on the tube.

As an ironic sign of the scheme’s success, the poems have reverted from the walls of tube trains and back into books. They are still in the trains of course, but 100 Poems on the Underground was published in 1991 and different versions and collections have been published frequently since. These books sell well, and one must assume that a good number of the purchasers are people who have been inspired by reading poems on the tube.

Of course poets and writers have championed the work of Poems on the Underground, praising the democratisation or poetry and the subtle contribution the poems make to the cultural life of the city. Poet Imtiaz Dharker wrote:

When I saw my first Poem on the Underground decades ago, I was so taken with the poem and the idea of reading it on an underground carriage that I missed my stop. It was only years later, when my own poem went up on the underground, that I understood the drive behind it: an absolute belief in the necessity of poetry, its power in the places where we live and travel every day.

The scheme as been deemed significant enough to be archived and catalogued by Cambridge University. Its collection of papers includes posters, memorabilia and letters from some of the greatest poets of the past century. There are letters from Nobel Prize winners Seamus Heaney and Louise Glück, former Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy, Philip Larkin and many others.

Dissenting Voice

So it may be surprising to read that the ‘bad tube poetry’ is a ‘scourge’. To be fair, Finn McRedmond is not arguing that all the poetry is bad, but that some of it is banal:

By elevating the bad and discrediting the good, Poems on the Underground has diminished the public realm.

Her central premise is that the setting of the underground does poetry no favours, that it is diminished by its proximity to advertising, to noise, to the rhythms of commuting. It’s poetry down the tube rather than on the tube.

But perhaps she misses that being taken out of those routines, being given the opportunity just to concentrate, and read, and think for a moment, is what many of these poems offer. Even if we dismiss one as trite, we’ve been through the process of evaluation and making that judgement, and the next poem might be more rewarding.

Other bits and pieces

Michael Billington considers the continuing appeal of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, in anticipation for the latest production with Ben Wishaw and Lucian Msamati.

Lisa Allardice has a short look at the Booker longlist.