Rotten Oranges: The Commodification of Women in Much Ado

It is not surprising that Much Ado About Nothing is usually remembered as the play about Beatrice and Benedick, the wittily sparring couple, rather than about Hero and Claudio, whose relationship forms the backbone of the plot. The verbal life of the play, as well as much of its physical humour, lies with Beatrice and Benedick, whereas Shakespeare gives Hero little sense of life or identity. She seems to function merely as a dramatic device, much in the same way as she is used as an object by the men in the play. Perhaps that is Shakespeare’s point.

In the play, Shakespeare presents us with a world of male bravado, ladz bantz and swagger. At the very beginning, the men are expected, returning from battle, the archetypes of masculinity, full of praise for those who have performed well in the ‘action’ and demonstrated ‘the feats of a lion’.

A whiff of back-slapping misogyny is immediately apparent once the men arrive, the elderly Leonato ingratiating himself with the younger Don Pedro by making a joke at the expense of his wife, who has assured him ‘many times’ that Hero is his daughter. It is a casual joke about women’s infidelity, but of course it is part of the tone-setting for the later accusation of Hero. Crucially, Hero is present for this exchange about her parentage, but has no comment; indeed, although she is onstage from the outset, she has only one line in the entirety of the first scene.

A Jewel in a Case

Against this background of Hero seen, but not heard, Claudio’s initial discussion of her does not seem so out of place, but it is Benedick’s joking questions which reduce her to an item for purchase, asking Claudio ‘Would you buy her, that you inquire after her?’ And it is Claudio’s reply that reduces her to an inanimate bauble, ‘a jewel’. Significantly, he assures Benedick that Hero is ‘the sweetest lady that ever I looked on’ – she is a visual treat only, like the jewel.

This portrayal of Hero as an attractive object, for the admiration and possession of men, continues through the play. On discovering Claudio’s attraction to Hero, Don Pedro immediately offers to act as intermediary. ‘I will break with her and with her father,’ he says, ‘And thou shalt have her.’ Such negotiations between men about the marital position of a woman of rank would not, of course, have been unusual in Elizabethan England or Renaissance Europe. Seeking the father’s permission would have been customary and Claudio has the advantage of a prince to vouch for him. Nevertheless, Don Pedro’s confident assertion of success, when so little has been heard from Hero herself, is uncomfortably striking, especially for a modern audience, accentuated by his use of the possessive verb ‘have’.

Don Pedro’s ploy of courting Hero in disguise takes things further. Perhaps Pedro believes he has a sweeter tongue than the callow Claudio and is more likely to achieve success with his ‘amorous tale’, but it is an ambiguous suggestion, opening itself to just the type of misinterpretation which Don John plays on. It is a distinctly odd idea, and furthers the idea of Hero as a plaything for the men, reinforced by his projected conclusion to the plan, with its note of possession again: ‘she shall be thine.’ When Leonato is given the wrong end of the stick and believes Don Pedro is courting Hero himself, his instruction to her is clear: ‘remember what I told you: if the prince do solicit you in that kind, you know your answer.’ Her uncle Antonio too weighs in, saying ‘I trust you will be ruled by your father.’ The language is again indicative: Leonato is giving Hero a clear instruction. The phrase ‘you know your answer’ ironically points out that this knowledge only comes from her father; she is subject, as Antonio points out, to his ‘rule’. And Shakespeare gives no lines at all to Hero in this exchange; neither of her mere two lines so far in the play has indicated anything about her own wishes.

Don John’s Tricks

Since the men closest to Hero have so little regard for her views, it is not surprising that Don John sees her merely as a means to an end, a tool to antagonise Don Pedro. ‘If I can cross him any way,’ he says, ‘I bless myself every way.’ Hero is merely a ‘way’, expendable grist to his mill.

Don John’s first failed attempt to sow discord, Claudio led to believe that Don Pedro has sought Hero for himself, results in Claudio’s sulky petulance. The idea that Pedro has stolen an object from him is emphasised by Benedick’s jokes about stealing ‘your meat’ and his ‘bird’s nest’. While this confusion is quickly resolved, the audience might note that there is not a single exchange of dialogue between Claudio and Hero – in fact Hero does not address a single line to Claudio until he accuses her in Act 4.

Don John’s second, more elaborate, trick is of course successful. Although, interestingly and significantly, Shakespeare chooses not to stage the encounter between Borachio and Margaret, his description makes clear the elements of performance. The audience of Don Pedro and Claudio are to watch something, from a distance, with one or two lines of dialogue thrown in. Again Hero (though it’s not actually Hero this time) is a distant, visual object. Claudio’s belief in her loyalty, based on not very much, is quickly overturned by a man who has very recently been at loggerheads with Don Pedro. Male trust trumps faith in the female.

Even so, Shakespeare shocks the audience with the sudden coldness and determination of the plan of revenge. The impact is particularly strong because it is not a plan made in a crisis of emotion at the discovery of Hero’s apparent falseness, but one made in advance after a short dialogue with Don John:

CLAUDIO: If I see any thing to-night why I should not marry her to-morrow in the congregation, where I should wed, there will I shame her.

DON PEDRO: And, as I wooed for thee to obtain her, I will join with thee to disgrace her.

Note the determined future tense of ‘there will I’ and ‘I will join’ and the two verbs ‘shame’ and ‘disgrace’ applied to ‘her’ – Hero.

Wedding Humiliation

That they take this revenge by staging the shaming at the wedding service itself is shocking callousness. There are many uncomfortable moments in Shakespeare’s comedies, but surely none so appalling as this. While Shakespeare mitigates it through dramatic irony – we know Hero is innocent and that the culprits have already been apprehended – this does not lessen the horror of the moment for Hero or the brazen viciousness of Don Pedro and Claudio. Instead of an exchange of vows, we get an outpouring of insults. It is notable how the language again points to objects and possession. Claudio asks of Leonato whether he ‘Give[s] me this maid’ and equates her ironically with a ‘rich and precious gift’. Then Claudio defines Hero in his own terms as ‘this rotten orange’ and ‘a common stale’, both images suggesting rank corruption. The earlier ‘jewel’ is now disfigured and discarded.

That they take this revenge by staging the shaming at the wedding service itself is shocking callousness. There are many uncomfortable moments in Shakespeare’s comedies, but surely none so appalling as this. While Shakespeare mitigates it through dramatic irony – we know Hero is innocent and that the culprits have already been apprehended – this does not lessen the horror of the moment for Hero or the brazen viciousness of Don Pedro and Claudio. Instead of an exchange of vows, we get an outpouring of insults. It is notable how the language again points to objects and possession. Claudio asks of Leonato whether he ‘Give[s] me this maid’ and equates her ironically with a ‘rich and precious gift’. Then Claudio defines Hero in his own terms as ‘this rotten orange’ and ‘a common stale’, both images suggesting rank corruption. The earlier ‘jewel’ is now disfigured and discarded.

Of course in this man’s world, male trust again comes to the fore as Leonato, rather than defend his daughter, commands her in her swoon not to ‘ope thine eyes’ and wishes to ‘let her die.’ Even the Friar’s sympathetic plan, based on his belief in Hero’s ‘maiden truth’, for her to be ‘secretly kept in’ to make it appear ‘that she is dead indeed’, sets her up again as the subject of men’s tricks. And again, she has nothing to do with the planning and is not asked for her view. After protesting her innocence to her father, Hero has no further lines until the latest trick’s denouement, when she is revealed again before Claudio in the final scene of the play, after being paraded as the mystery cousin behind a mask. Even at this point of the play, Claudio’s language indicates possession, asking which lady he ‘must seize upon’ and claiming ‘she’s mine.’

Hero’s Dullness

One would think, with all this evidence, that Hero would be a most dispiriting part for an actor to play – a compliant object, paraded, displayed, tricked and abused – before marrying her chief abuser. The final marriage between Claudio and Hero is quite tricky to swallow, giving the end of Much Ado an ambiguity akin to the undercut joy of the end of Twelfth Night. It is notable that when she is revealed, she speaks only of her own innocence; Shakespeare gives her no lines which address her feelings about Claudio, or marriage. In fact, he gives her no lines about her feelings for Claudio in the entire play, with just one reference comparing Benedick to ‘my dear Claudio’ during the tricking of Beatrice. Indeed, before her initial wedding ceremony, she confesses that ‘my heart is exceeding heavy.’

So is Hero just a dull character? It would be easy to dismiss her as one of Shakespeare’s less effective portrayals of women, but in fact she does show spark and wit – just never in relation to or in conjunction with Claudio. There is a touch of witty sparring with the disguised Don Pedro at the party and Shakespeare shows her at her liveliest when preparing and carrying out the deception of Beatrice with Ursula and Margaret. Here at the beginning of Act 3 she has her only speeches of any length. She is the instigator of the plan and directs Margaret and Ursula in it, taking control through imperatives: ‘run thee’, ‘Whisper her ear’, ‘say that’, ‘This is thy office’, ‘let it be thy part’, ‘Now begin’. She leads the praise of Benedick and disparagement of Beatrice to make the plot work; Ursula merely responds and feeds lines. The spirit and wit she displays in the middle of the play demonstrate that she is an interesting and attractive character. Her characterisation in the play as a whole, then, suggests that Shakespeare shows that a woman is rendered lifeless by courtship and marriage – at least by the conventional family-arranged marriages of the time.

An Alternative Relationship

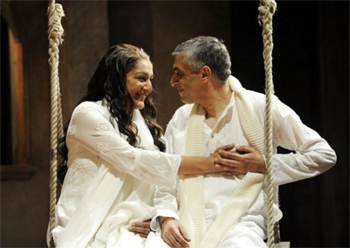

This is accentuated by the very clear contrast Shakespeare creates between the Hero/Claudio relationship and the one between Beatrice and Benedick, and why these latter lovers are the stars of the play. They start cantankerously opposed not just for the humour of their barbed jests, but to show that their union is one that has been arrived at, through knowledge and recognition, not through distant admiration and proxy wooing.

Just as their arguments and insults are balanced, each giving as good as they get, so their love is paralleled. Even the two comic scenes of contrived overhearing, which bring each of Beatrice and Benedick to the realisation of their mutual attraction, are mirror images of each other. Significantly, Beatrice’s response to overhearing Hero and Ursula is ‘Benedick, love on; I will requite thee’, the word ‘requite’ suggesting balanced reciprocation.

Just as their arguments and insults are balanced, each giving as good as they get, so their love is paralleled. Even the two comic scenes of contrived overhearing, which bring each of Beatrice and Benedick to the realisation of their mutual attraction, are mirror images of each other. Significantly, Beatrice’s response to overhearing Hero and Ursula is ‘Benedick, love on; I will requite thee’, the word ‘requite’ suggesting balanced reciprocation.

Benedick explicitly rejects conventional courtship, saying that he ‘cannot woo in festival terms.’ He shows his love in a much more striking manner, in response to Beatrice’s shocking command ‘Kill Claudio.’ He breaks out of the male world of mutual trust and support and agrees to challenge his best friend. Note the pairing of his intentions in ‘I will challenge him. I will kiss your hand’.

The exposure of Borachio’s and Don John’s plot saves him from the duel, but that challenge is made, where he is cast in a far more favourable light that the heartless jesting Claudio. While it is indeed ‘strange’, as Benedick puts it, that he and Beatrice are in love, and that they ‘are too wise to woo peaceably’, Shakespeare has made his point. But he seals it with their neatly parallel speeches towards the end of the play:

BENEDICK: Do not you love me?

BEATRICE: Why, no; no more than reason.

BEATRICE: Do not you love me?

BENEDICK: Troth, no; no more than reason.

Here Shakespeare presents us with a relationship we can respect, based on reason, knowledge and understanding, rather than distant objectification which can lead to misunderstanding. And in this kind of relationship, the woman is equal to the man – feisty, opinionated and outspoken rather than a commodity.

Further listening

Listen to Emma Smith, from Oxford University, in her podcast on the play.