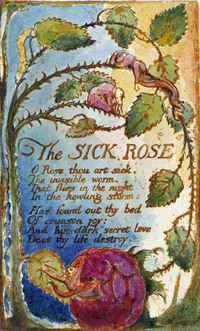

Here’s a poem by William Blake, from his Songs of Experience:

The Sick Rose

O Rose thou art sick.

The invisible worm,

That flies in the night

In the howling storm:

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy:

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

This address to a rose, lamenting its sickness caused by an invading worm, is clearly not about a flower. Or not just about a flower, because at a literal level, the destruction of a beautiful flower by a worm or more likely a worm-like caterpillar, is the frustration of many gardeners.

But few gardeners would bother to address the afflicted rose in such terms, so it is quickly clear that the rose, and the worm, are representative of something else, bigger than themselves. Then throw in the night, the howling storm and the bed, and the range of possible readings becomes broader.

So Blake’s poem is an allegory:

Allegory (Merriam Webster dictionary)

- the expression by means of symbolic fictional figures and actions of truths or generalizations about human existence

- an instance (as in a story or painting) of such expression

- a symbolic representation

In order to read the symbolic representation, we have to pick up associations and connotations. We are likely to connect roses with love, and with the ‘bed/ Of crimson joy’ that is extended to sexual love. The worm is also frequently used with phallic suggestions (see Marvell’s ‘To His Coy Mistress’), which make the ‘howling storm’ suggestive of passion. (Note that the worm on the branch in Blake’s own illustration seems to have human form.) Does sexual passion, then, ‘destroy’ the rose’s life? This is unlikely, since the joyful crimson bed pre-exists the worm’s arrival. The worm’s love is ‘dark’ and ‘secret’, both foreboding adjectives. It is unlikely, given his views, that Blake is suggesting that sex itself is corrupting, so is it that the love is ‘dark secret’ which makes it a source of corruption? We might then consider why the love is secretive and hidden, and we could arrive at a forbidden love, restricted by family pressures, social morality or religion, all of which are possibilities for the time Blake in which was writing and would resonate with his other poetry.

You will note that the interpretation is not definite; the reader has to balance the suggestions and associations of words and imagery, with some consideration of the context of the writing, to arrive at a conclusion. Different readers, though, might arrive at differing conclusions. This is inevitable when we are not looking at a purely literal text where the author hints at meanings rather than states them. And that makes the texts fascinating to read, to think about, to discuss.

Blakes’s poem is a very short allegory, useful for illustration. Allegories also exist in drama, film and the visual arts and you may be aware of some literary ones already, such as Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible (production photograph from a performance in Canberra left), William Golding’s novel The Lord of the Flies, George Orwell’s Animal Farm and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. Not all are written explicitly as allegories, but attract allegorical readings.

Blakes’s poem is a very short allegory, useful for illustration. Allegories also exist in drama, film and the visual arts and you may be aware of some literary ones already, such as Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible (production photograph from a performance in Canberra left), William Golding’s novel The Lord of the Flies, George Orwell’s Animal Farm and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. Not all are written explicitly as allegories, but attract allegorical readings.

Try this list of ‘Top 10’ literary allegories, chosen by Adam Biles in The Guardian.