While the famous diaries of Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) give us intriguing insight into the world of 17th century London, they also reveal his business dealing, his womanising and his interest in clothes. As the son of a washerwoman and a tailor, perhaps this is not surprising. As well as his diaries, among his papers was a collection illustrative prints of French fashions, demonstrating further Pepys’ fascination with couture.

While the famous diaries of Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) give us intriguing insight into the world of 17th century London, they also reveal his business dealing, his womanising and his interest in clothes. As the son of a washerwoman and a tailor, perhaps this is not surprising. As well as his diaries, among his papers was a collection illustrative prints of French fashions, demonstrating further Pepys’ fascination with couture.

This collection has been studied by Cambridge historian Marlo Avido, who has compared the illustrations with what Pepys has to say about clothing and fashion in his diaries and that together they reveal his concern for clothes, their appearance and what they suggest about one’s station in life.

Theatre Attendance

As a fashionable man about town, Pepys was a frequent audience member at the theatre in London. He saw performances of Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist at least three times, judging it ‘a most incomparable play’ on 22 June 1661 and being particularly impressed by the actor Walter Clun, whose violent death he lamented on 4 August 1664.

He also saw Jonson’s The Silent Woman, now more usually known as Epicoene, at least twice, and was particularly impressed the first time he saw it on 7 January 1661:

The first time that ever I did see it, and it is an excellent play. Among other things here, Kinaston, the boy; had the good turn to appear in three shapes: first, as a poor woman in ordinary clothes, to please Morose; then in fine clothes, as a gallant, and in them was clearly the prettiest woman in the whole house, and lastly, as a man; and then likewise did appear the handsomest man in the house.

Pepys’ careful recording of elements of the plot performed by Edward Kynaston, one of the last Restoration boy actors playing women’s roles, demonstrates how much he was impressed by the performance.

He was less impressed by a production of Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair on 8 June 1661, however. Although Pepys admitted that ‘It is a most admirable play and well acted’, he was concerned that it was also ‘too much prophane and abusive.’

Shakespeare Shows

Inevitably, Pepys saw a number of Shakespeare’s plays, as he was attending performances a mere 44 years after the playwright’s death. On 5 December 1660, for example, he saw The Merry Wives of Windsor, with mixed responses. ‘The humours of ‘the country gentleman and the French doctor [were] very well done’, he opined, ‘but the rest but very poorly, and Sir J. Falstaffe as bad as any’. Things weren’t much better on 25 September the following year, when he saw the play again and judged it ‘ill done’.

Hamlet, seen on 27 November 1661, fared better, Pepys considering it ‘very well done’, and he thought Henry IV, seen on 4 June that year, to be ‘a good play’.

Shakespeare’s final play The Tempest, often seen as his self-referential sign-off from the theatre, was less successful in Pepys’ eyes. He saw it on 7 November 1667 and wrote in his diary:

The house mighty full; the King and Court there and the most innocent play that ever I saw; and a curious piece of musique in an echo of half sentences, the echo repeating the former half, while the man goes on to the latter; which is mighty pretty. The play [has] no great wit, but yet good, above ordinary plays.

‘Above ordinary plays’ indeed! That is what we might call ‘damning with faint praise’.

However, even The Tempest fared better than A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which Pepys saw on 29 September 1662. He remembered the event like this:

However, even The Tempest fared better than A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which Pepys saw on 29 September 1662. He remembered the event like this:

I sent for some dinner and there dined, Mrs. Margaret Pen being by, to whom I had spoke to go along with us to a play this afternoon, and then to the King’s Theatre, where we saw “Midsummer’s Night’s Dream,” which I had never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life. I saw, I confess, some good dancing and some handsome women, which was all my pleasure.

It does seem typical of Pepys that he appreciated the dancing girls, but not the action, exploration of love and witty word-play of the Dream.

John Dryden

Samuel Pepys knew Dryden at Cambridge and he clearly preferred the more contemporary writer, though now Dryden’s reputation as a dramatist pales before that of Jonson and Shakespeare. On 2 March 1667 he saw The Maiden Queen, commending its ‘strain and wit’, and judging the performance by Nell Gwyn as one that he could never hope ‘to see the like done again, by man or woman.’

He did note that his wife did not enjoy Dryden’s play Evening Love, but Sir Martin Mar-all Pepys judged to be:

…the most entire piece of mirth, a complete farce from one end to the other, that certainly was ever writ. I never laughed so in all my life. I laughed till my head [ached] all the evening and night with the laughing; and at very good wit therein, not fooling. (16 August 1667)

But who today has heard of Sir Martin Mar-all rather than The Alchemist, The Tempest or A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Bibliophile

As a wealthy and cultured man, Samuel Pepys was fond of his books, compiling a considerable library. On 10 December 1663 he recounted a pleasant day at the bookshop:

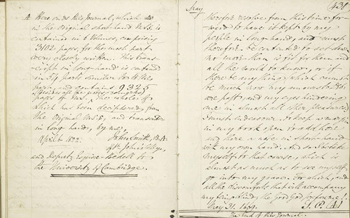

Thence to St. Paul’s Church Yard, to my bookseller’s, and having gained this day in the office by my stationer’s bill to the King about 40s. or 3l., I did here sit two or three hours calling for twenty books to lay this money out upon, and found myself at a great losse where to choose, and do see how my nature would gladly return to laying out money in this trade. I could not tell whether to lay out my money for books of pleasure, as plays, which my nature was most earnest in; but at last, after seeing Chaucer, Dugdale’s History of Paul’s, Stows London, Gesner, History of Trent, besides Shakespeare, Jonson, and Beaumont’s plays, I at last chose Dr. Fuller’s Worthys, the Cabbala or Collections of Letters of State, and a little book, Delices de Hollande, with another little book or two, all of good use or serious pleasure: and Hudibras, both parts, the book now in greatest fashion for drollery, though I cannot, I confess, see enough where the wit lies. My mind being thus settled, I went by linke home, and so to my office, and to read in Rushworth; and so home to supper and to bed.

According to his diaries, he often finished the day by reading, so he needed plenty of material.

You can explore Samuel Pepys’ diaries online here.