Kae Tempest’s Brand New Ancients, which takes ordinary people and sees their lives in the light of the ancient Greek myths, is a powerful, rhythmic tour de force. It’s a lengthy rap which has become established on the edges of the literary canon, and its vibrant appeal to students has ensured it has become a regular text analysed in A Level coursework. Raw and uncompromising, it deals directly with the vicissitudes of contemporary life but raises its characters to mythic figures. Crucially, there is understanding and even sympathy for everyone – even the villains. As the poem says in a crucial line:

Kae Tempest’s Brand New Ancients, which takes ordinary people and sees their lives in the light of the ancient Greek myths, is a powerful, rhythmic tour de force. It’s a lengthy rap which has become established on the edges of the literary canon, and its vibrant appeal to students has ensured it has become a regular text analysed in A Level coursework. Raw and uncompromising, it deals directly with the vicissitudes of contemporary life but raises its characters to mythic figures. Crucially, there is understanding and even sympathy for everyone – even the villains. As the poem says in a crucial line:

A god becomes a god when he has the guts to love.

That is quite a striking line and speaks of Tempest’s openness, a willingness to engage constructively rather than rage destructively. In an interview, they developed this view:

What the Government is doing to the country, what is happening to people, in terms of really difficult living conditions, as a direct result of people who are so removed from understanding the effects that their policies are having, so removed from the reality, like – the instinct is to hate them. But that’s not going to get me anywhere, or them. And the divisions between people are the reason that we’re in such a mess.

In times when discord and vilification are fanned by social media, your opponents are dismissed as ‘vermin’ or your online spat ends up in court, that is quite a remarkable view. There is no doubting the truth of that last sentence.

From Kate to Kae

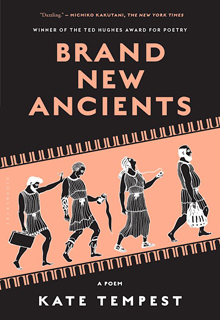

Perhaps that determination to love, rather than hate, comes from years of self-hate as Tempest struggled with identity. Brand New Ancients, as the illustration shows, was published in 2013 by Kate Tempest. It was seven years later that they dropped the ‘t’ from Kate and revealed they were non-binary.

That decision is the starting point for the recent BBC Arena documentary Being Kae Tempest, which follows that decision. While there is plenty of flashback footage of Kate’s arrival on the spoken word and rap scene, the film’s main focus is on collaborations and performances since, which reveal the constant work in various forms and the peace gained from that decision.

One review refers to the film as a ‘pleasingly hype-free documentary’ which ‘shows them in a far happier place than in recent years’. As the review says, we see episodes of mundane content ordinariness as well as performances on stages such as Glastonbury. Importantly, we see the seriousness with which they go about their writing:

Being Kae Tempest’s main preoccupation is the day-to-day reality of their career: this is a portrait of the artist as a workaholic. We witness Tempest editing poems backstage at gigs, juggling play writing, novel writing, lyric writing and more.

Watch the film on BBC iPlayer here.

That all-consuming passion for writing is very evident in the interview linked above. Tempest acknowledges the debt they have to other writers – ‘if you’re a writer, you want to read the best ones’ – and WB Yeats, Ursula Le Guin, George Orwell, Mervyn Peake and Graham Greene are mentioned, as well as William Blake being a primary inspiration.

That debt to previous writers is something Brand New Ancients depends on, leaning as it does on the Classics. As Tempest says, ‘I work extremely hard, trying to learn things, trying to read up on mythology or whatever it is’.

Performances and Reviews

You can read excerpts from the poem on the Poetry Society site and see clips of Tempest performing the work live on their YouTube channel. There are some thoughts on the poem here, and there are a couple of interesting reviews of earlier performances. This one pays tribute to the characterisation, arguing that what might ‘have been undeveloped stereotypes’ are in Tempest’s poem ‘shaped into the modern, almost mythic, and oh so real characters that burst out of this piece’. The New York Times suggests that Tempest’s ‘hypnotically persuasive vision’ is reconnecting theatre with its roots in oral storytelling. The final comments on Tempest as ‘petite’ and ‘girlish’ with ‘English-rose loveliness’, however, now appear inappropriate and ironic. But the observation that, ‘While she moves casually across the stage, she often seems to be vibrating like a tuning fork with the urgency of the telling’, is spot-on.

You can read excerpts from the poem on the Poetry Society site and see clips of Tempest performing the work live on their YouTube channel. There are some thoughts on the poem here, and there are a couple of interesting reviews of earlier performances. This one pays tribute to the characterisation, arguing that what might ‘have been undeveloped stereotypes’ are in Tempest’s poem ‘shaped into the modern, almost mythic, and oh so real characters that burst out of this piece’. The New York Times suggests that Tempest’s ‘hypnotically persuasive vision’ is reconnecting theatre with its roots in oral storytelling. The final comments on Tempest as ‘petite’ and ‘girlish’ with ‘English-rose loveliness’, however, now appear inappropriate and ironic. But the observation that, ‘While she moves casually across the stage, she often seems to be vibrating like a tuning fork with the urgency of the telling’, is spot-on.

Like Blake, or like Shelley, who saw poets as ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’, Tempest is strongly aware of both the social function of the arts, but also the extra perception that a writer must have:

I feel like when you’re a writer you’re tuned in to the world at a particular frequency where your sensitivity is so raw and everything you see in your journey through the city is such an onslaught of either, like, unbearable beauty or, you know, unbearable horror.

You can hear Tempest performing some of her work on the Poetry Archive and here is Kae Tempest’s own website.