Marghanita Laski

There is a wonderful developing spookiness to Laski’s tale, beginning in such an ordinary way and ending with understated terror. The reader shares in that terror, as although the story is narrated in the third person, it closely focalises Caroline’s perspective. That begins without warning in the first paragraph, which we read, with Caroline, from a travel guide. The informative style is immediately recognisable, with description of the ‘pleasing olives and vines’, the directions, and the parenthetical placement of extra detail – ‘(470 steps)’. That serves as a narrative trick. The style is so like a guidebook, the detail so innocuous-sounding, that the reader does not realise that it is a key piece of foreshadowing.

The Mystery of Giovanna di Ferramano

There are other little clues, like the ominous title of ‘the Tower of Sacrifice’ and the destruction of the village. These are developed later, when in flashback, the narrative recounts the conversation between Caroline and her husband Neville about the portraits of Giovanna and Niccolo di Ferramano in a private gallery. With references to Giovanna’s early marriage and death, the mystery surrounding her husband and the suggestions of his involvement with the occult, Laski creates a strong sense of unease. She adds Neville’s uncertainty over whether Giovanna was ‘lost’ or ‘damned’ in the Count’s story. Threads across the story interconnect when Neville claims a connection between Giovanna and Caroline – ‘Do you know, she’s rather like you.’ Laski uses the adverb ‘casually’ for Neville’s comment, but it could be equally well applied to Laski herself and the almost offhand way she makes the link between the two women through a stray comment of dialogue.

Climbing the Tower

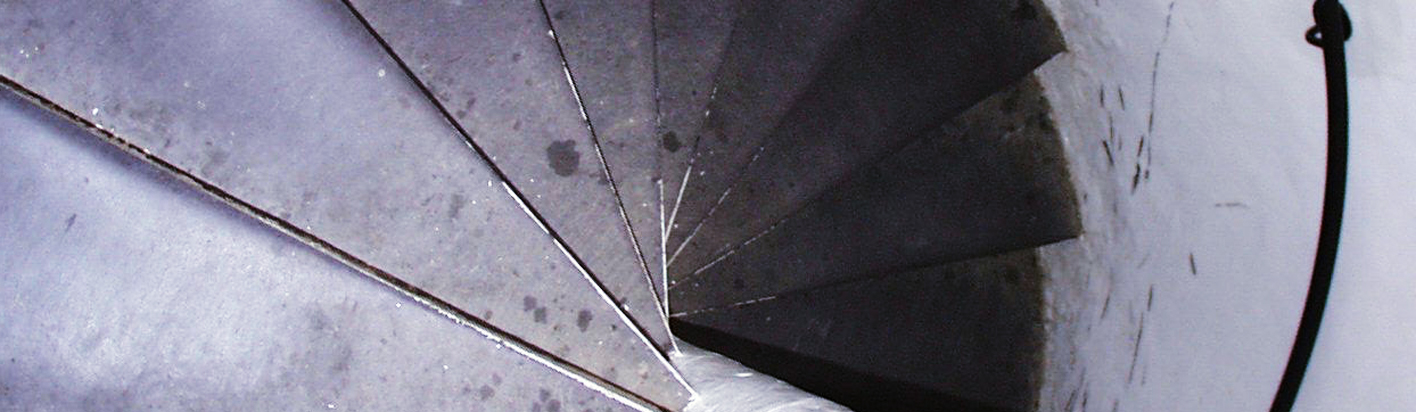

Laski builds the importance of those 470 steps as Caroline climbs the tower. Her counting of the steps punctuates the final pages of the story. A sunny day in the Tuscan countryside could not be less gothic, but as soon as Caroline enters the tower and begins her climb, the mood changes, acquiring gothic elements and a growing sense of claustrophobia. There are immediate constrictive architectural details such as the ‘low arched ceiling’ and the ‘narrow stone staircase’. Each window is only a ‘narrow slit’ and as Caroline notes, it gets ‘dark very quickly.’ The breaks in the ‘rusty’ handrail increase the tension, as does Caroline’s counting of the steps. As the reader shares Caroline’s consciousness, we are also aware of her increasing doubts – ‘It would be much more sensible to give up and go home’ and ‘I really ought to go down now’. Laski also uses verbs carefully; as Caroline ‘climbed’, she also ‘groped’, ‘pressed tightly’, ‘clutched’ and ‘fumbled’, all of which indicate a lack of physical security.

The Descent

Even though Caroline has climbed in the expectation of ‘a wonderful view at the top’, Laski makes no mention of a view at all; Caroline is only conscious of how ‘immeasurably, unbelievably high’ she is – it is terrifying rather than ‘wonderful’. Ominously she has to resist the ‘impulse to hurl herself’ from the top. The descent is so painful that Laski devotes six paragraphs to six steps. The language in this section is much more intense, with adjectives such as ‘unprotected’, ‘disappearing’ and ‘menacing’ for the staircase, verbs like ‘screamed’, ‘staring’ and ‘tearing’ with adjectives and adverbs like ‘shuddering’, ‘stupefied’ and ‘tightly’ for Caroline. While bats are traditional inhabitants of dark gothic spaces, Laski’s description of them, with three instances of the word ‘horror’ and the evocative ‘whispering skin-stretched wings’, makes them repellent. While Laski uses speech marks for Caroline’s internal dialogue and her counting the steps, she makes the internal voice urging her to death much more direct, with no speech marks: ‘It would be much easier to fall, said the voice in her head… You cannot climb down.’ While she overcomes this voice and compels herself to descend slowly, Laski keeps the real horror for the last few words, the continuing step count – ‘five hundred and two – and three and four –’ Significantly, not only is the count never completed, but Laski does not even end with a full stop.

The Gothic and Gender

In gothic literature, extreme states of fear are often used to explore the psychology of the protagonist and the setting is often instrumental in this. Looking at this story in Freudian terms, it is not hard to see the tower as a phallic symbol, representing masculinity. Caroline sets out to climb it, to conquer it, but instead is overwhelmed by it. If we look back through the story, we can recognise Laski’s careful threading of gender concerns. The first word of the second paragraph is ‘Triumphantly’. Caroline’s triumph is one of independent success – independence from husband Neville, who in his well-meaning way has stifled her. The language used to describe Caroline suggests caution and uncertainty – ‘hesitantly, haltingly… managed to piece out…’ – while Neville ‘was always urging’ her to take the guidebook, he was ‘certain to know all about the campaniles’. Subtly, Laski makes the portrait of this knowledgeable, intelligent man quite unattractive. He has ‘brought’ Caroline to Florence, as if she were an item in his hand luggage. His knowledge of culture seems acquisitive, as he wants ‘to accumulate Tuscan culture for himself’. He dismisses Caroline’s idea of visiting galleries with contempt; to him they contain merely ‘stuff’, whereas he has access to ‘privately owned’ culture. He never notices that his wife does not share his passions, that she is ‘almost anaesthetized to Italian art.’ His mini-lectures in this ‘well-bred voice’ are mocked as examples of ‘dissertation’.

It is very appropriate, therefore, that the portraits of Giovanna and Niccolo di Ferramano are the subjects of their discussion. Caroline’s response to Giovanna’s painting is personal, emotional; she reacts to the woman herself, married and dead at eighteen. Neville is academic and detached, able to supply historical context – ‘They married young in those days’ – and is able to interpret the clues in the painting of Niccolo. Again, Caroline’s reaction is personal: ‘I don’t like him’. We have a young wife and a husband who is interested in culture and books discussing portraits of a young wife and her husband, who is painted with his hand on a pile of books. Laski is making a very clear parallel between the two couples. Caroline is empathetic towards Giovanna and Neville himself makes the connection between them. Although shrouded in mystery, the dark arts of Niccolo are clearly linked with the death of his wife and the destruction of the village around the ‘Tower of Sacrifice’. We should note too that an English translation of the name ‘Ferramano’ would be ‘iron hand’, another indicator of inflexible masculine control. Caroline’s never-ending descent into the bowels of the tower confirm the link between herself and Giovanna and a story about women controlled by men.

Narrative methods to consider:

- Focalised third person narration

- Structure

- Symbolism

- Gothic elements

- Twist/surprise